Dillon History

Dam Docent

On the fiftieth anniversary of the flooding of Dillon, a professor revisits Summit County’s Atlantis.

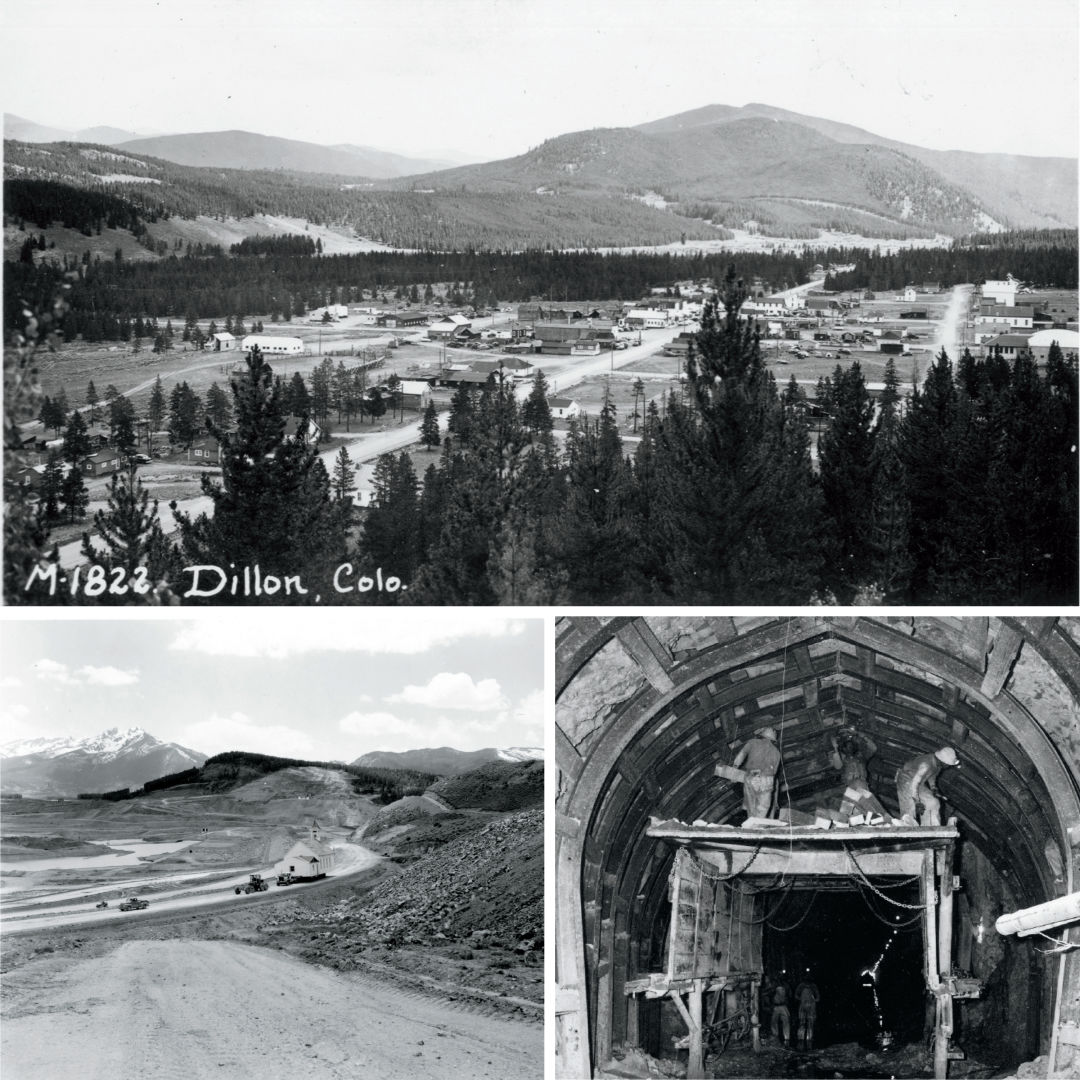

Clockwise from top: The Town of Old Dillon; relocating Dillon Community Church; digging the mouth of the tunnel that sends lake water to Denver.

Image: Courtesy: Denver Water

Every summer, Sandie Mather loads her RAV4 seats-to-ceiling with broad-brimmed hats, woolen skirts, lacy nineteenth-century blouses, and books, then drives 1,700 miles from her home in Avondale, Penn., to a rented condo in Summit County.

The costumes help transform her into Breckenridge pioneer Anna Sadler Hamilton, whom Mather portrays as a re-enactor in the Summit Historical Society’s “Pastry and the Past” lecture series. The books (They Weren’t All Prostitutes and Gamblers, Roadside Summit Part I: The Natural Landscape, Roadside Summit Part II: The Human Landscape, and particularly relevant this summer and fall, Dillon, Denver and the Dam) get peddled at the Dillon Farmers Market, where every Friday morning she resumes her real-life role as author and West Chester University emerita professor of geology and astronomy, an educator devoted to exploring and explaining the ways humans have reshaped the landscape of Summit County.

“Physical geography is the study of changes in the landscape over time,” Mather explains, bundled in a wool blanket at the SHS book table on the market’s opening day in late May, shrugging off a late-season snowstorm. “As a geologist and a geographer, I look out on the landscape, I see where everything is, and I ask why it’s there.”

Mather was in her thirties in 1975 when she visited Summit County for the first time and posed that very question to her husband. Married to a geography professor, she had just begun her own doctoral coursework in physical geography when the couple and two friends decided to take an impromptu spring-break ski trip to Colorado.

“I was the only nonskier in the bunch, so they put a map in front of me and said, ‘Sandie, you pick.’ And I closed my eyes and did this,” she recalls, plopping a gloved index finger onto the open page of one of her books, “and I landed on a town called Dillon. The four of us piled into a little Ford Pinto with our poles and skis and boots and everything, and we drove straight through from Pennsylvania to Dillon.”

Professor Sandie Mather, chronicler of Lake Dillon and the town it displaced.

Image: Ted Katauskas

The first thing Mather noticed from the highway was an enormous lake that, to the trained eye of a geographer/geologist, obviously didn’t belong.

“I saw it sitting there, and I knew there was a story to be told,” she says. “I drank the water. Around here, the joke is that if you drink the water, you’ll come back.”

And she did. Again and again, delving into the archives of state and local historical societies, mining a mountain of paperwork brittle with age, poring over ledgers, diaries, photographs, and blueprints. Mather’s chronicle of the history of the man-made lake, and the town it displaced, became her 300-page dissertation at the University of Oregon (“Landscape Change in Summit County, Colorado, from 1859 to Present”) and something of an obsession that became her life’s work. Ask her to condense all of that history into a single word, and she says, without hesitating, “resiliency.”

One myth she repeatedly busts is how Dillon earned its name. Conventional wisdom has it that the town was named in remembrance of a pioneer boy who wandered off into the wilderness. Hogwash, she says. The founders named their town after Sidney Dillon, the president of the Union Pacific, betting that flattery would bring the transcontinental railroad to town. (It didn’t, but still the town matured into Summit County’s agricultural and transportation hub, Mather says, noting that Dillon-grown vegetables once ended up on the plates of New York City restaurants.) The other legend she constantly dispels is that the ruins of the original town of Dillon can still be seen underwater near the dam—in fact, those buildings that weren’t relocated to New Dillon or elsewhere were demolished before the dam was topped off fifty years ago this July.

With few customers on this unseasonably cold May morning, Mather takes a break from her book sales and strolls to an overlook at Marina Park, where she stares out at the rocky crown of the dam (tailings from the twenty-three-mile-long tunnel that extends from beneath the lake toward Denver like an underground drinking straw), rising beyond the submerged original town.

“This is Denver’s water supply,” she says. “I think it’s gorgeous, I think it’s magnificent, but at the same time I understand that there are people—it’s a dwindling number—who look at the reservoir and see the death of a very old and comfortable way of life. I see beauty. I didn’t live to see Old Dillon, and that is to my regret.”

But with every book she sells, and on every Thursday morning when she leads a walking tour through the streets of New Dillon to pay homage to historic buildings rescued from the deluge fifty summers ago, she does her best to make the waters of time recede. csm