CYCLING

Trail of Gears

Ten hours of backbreaking toil a day under the blazing sun might sound like a prison sentence, but for the Town of Breckenridge's hard-pedaling crew of singletrack tenders, it's a dream job.

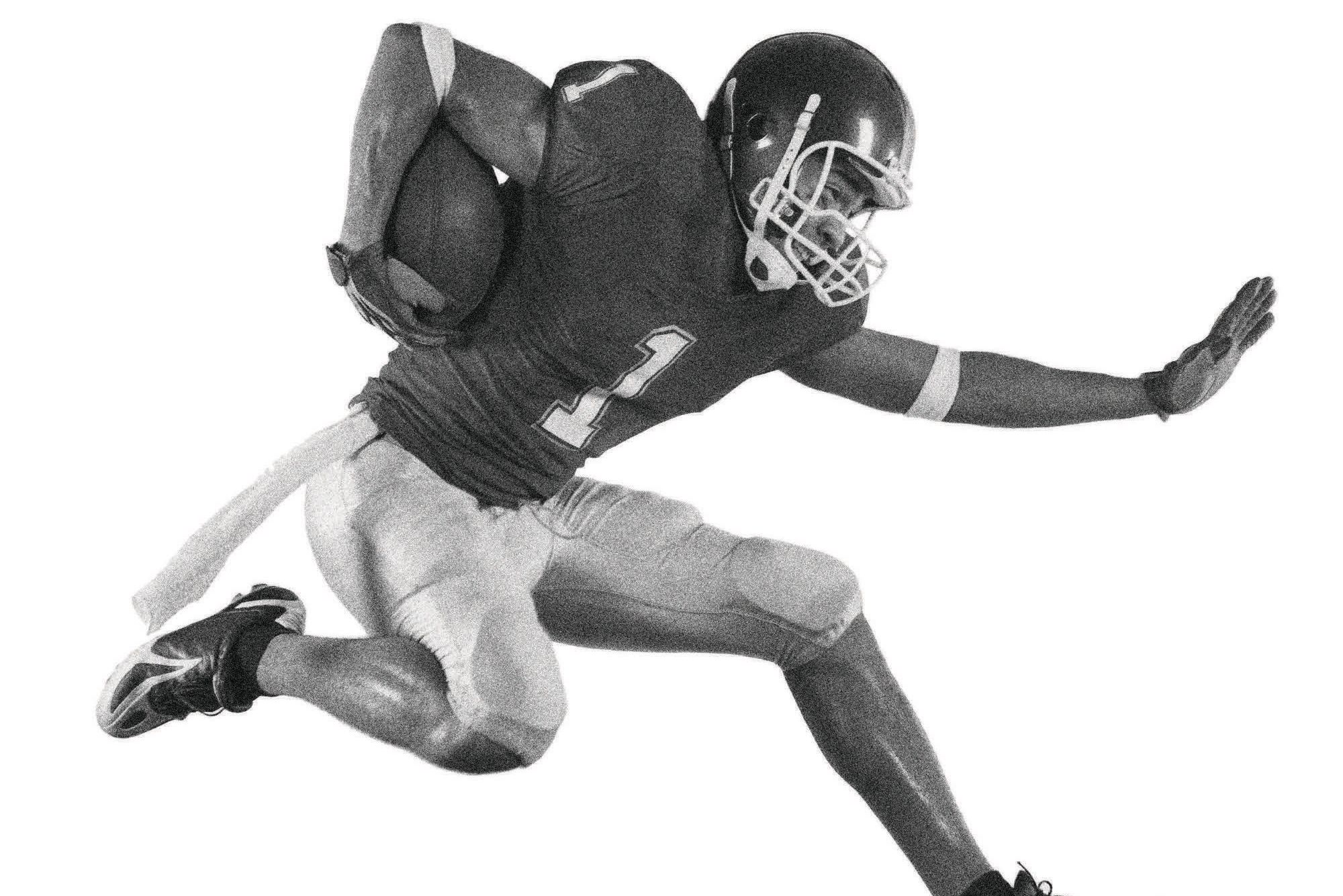

The crew, l-r: Dominic Muth, Tony Overlock, Lady Bugg, Joel Dukes, Ryan Walker, Nathan Guild, and Andrew Carney

Image: Mark Fox

It’s half past six in the morning, and Tony Overlock sits at the head of a long table in a darkened conference room in the bowels of Breckenridge’s town hall, flanked by five sturdy, mostly middle-aged men reaping calories from muesli and homemade “power cake,” clutching mugs of coffee like infants who have just graduated to sippy cups. A dog, Lady Bugg, dozes at their feet.

Despite the early hour, the mood is playful. It always is whenever this rugged corps gathers for a day of hard labor on the taxpayer’s dime, employed in what most in this bike-centric county would consider a dream job: getting paid to mint new backcountry singletrack and, as the need arises, test out the product by pedaling it. The third week in May marks their reunion as a unit, after a winter spent as snowmobile guides, ski patrollers, snowmakers, and ski techs. To prep for the season, Joel Dukes and Dominic Muth, the youngest of the crew at 30, spent the past week earning chain-saw certifications in Salida. Dukes explains the evaluation this way: “They watch you do some buckin’ and limbin’, then they watch you do some choppin’.”

Also in the room are fellow veterans Ryan Walker and Nathan Guild, as well as Andrew Carney, a new hire from Summit Cove who brings heavy-equipment experience plus an endurance-racing pedigree, highlighted by an eighth-place finish in the 2011 Colorado Trail Race, when he rode 480 miles and climbed and descended 70,000 vertical feet in five and a half days. For this job, such superhuman exploits rate almost as a prerequisite.

Since Breckenridge started employing full-time trail tenders in 2005, Overlock, a founding member, estimates the crew has blazed at least four miles of new trail per year, augmenting a web of 1800s mining roads and singletrack that essentially runs unbroken from Hoosier Pass to Dillon—and could get you to Denver or Durango via the Colorado Trail, which bisects the county just north of town. They build on land the town purchases for millions via a dedicated open-space sales tax; they also build on federal land, because the Forest Service doesn’t have the time or the resources.

Someone asks in jest why the town hired Carney over so many other hopefuls. (The rare opening on this crew typically draws 40 applications.) “We chose Andrew because he was good-looking and didn’t smell,” Overlock deadpans.

Moving on to other business, he delivers their marching orders: affix signs to fences to remind would-be users that certain trails remain closed for mud season, thereby protecting the town’s celebrated (and, in soggy May, especially vulnerable) network that extends hundreds of miles and is vast and varied enough to host three of the top distance races in the country: the six-day Breck Epic, the Breck 100, and the Firecracker 50, which kicks off the town’s Independence Day parade. That, and a singular important and daunting task: help complete a mountain-bike freeride park and pump track that is under construction in French Gulch. A cruel combination of wet weather and unseasonably bitter temperatures has left the site a mucky quagmire and made progress difficult. With a mid-June grand opening scheduled, the crew has much to do in a scant amount of time.

Overlock splits the group into two pods and assigns each a pickup truck. “Sound good?” he asks. “Let’s break.”

With that, everyone goes to work.

Trail crew boss and founding member Tony Overlock assesses progress on a pump track under construction in French Gulch

Image: Mark Fox

‘‘It’s going to be a small window between frozen dirt and peanut-butter soup,” says Dukes as he stands on the edge of Cucumber Gulch, a network of trails and pristine wetlands on Peak 8 that represents the crown jewel of the town’s open-space portfolio, anticipating the conditions they’ll find in French Gulch at the pump track. It’s only the second “trail closed” sign-posting stop of the morning, and already the two work pods have become one, deciding to stick together since they’ll all be wallowing in the muck at the pump track soon enough anyway—and since sticking together is more fun.

Though they josh each other and feign a service-time hierarchy (Overlock is “1,” Carney is “6”), they are effective because they work like an engine, with each man filling a role and none believing his role is more important than the rest.

Overlock and open-space planner Scott Reid—the latter more desk-bound than the field crew—are considered the visionaries. Carney and Muth bring machine experience. Dukes is a self-described “rock hunter,” who can turn a scree field into a wall before lunch. Guild prides himself on finish work. And Walker, who grew up in the Georgia hills and whom Dukes jokingly calls “Talker,” keeps the mood light.

“I gotta crack jokes,” says Walker. “Otherwise, it’s just throwing rocks.”

The crew (which, tangentially, also includes private contractor Troy Heflin, a former pro downhill racer who does machine work for the town) is decked out in town-supplied and trail-crew-branded apparel. Each wears a plaid button-down shirt and either jeans or Carhartts. Muth’s tall boots press against the bottom of his calves. Their gloves have their names written on them in marker.

When they arrive in French Gulch, one thing becomes patently clear: by the end of the day, everyone will look like a mud wrestler.

Earlier this spring, Overlock and Reid hired Elevated Trail Designs, a trail-construction firm based in Boulder and North Carolina, to design and build the pump track. Elevated co-owner Peter Mills was one of eight bidders for the job, which paid $26,000, not including materials. Mills was particularly happy to be building a signature feature in a signature mountain-biking town like Breckenridge. Thanks to the park’s location and a soon-to-be-built trail that will connect it to the downtown historic district, Mills and the town crew hope riders will incorporate it as part of their bigger backcountry loops, a rare combo to have in such close proximity.

“I used to live in Ashville, North Carolina,” Mills says, “and that’s a town that’s known for mountain biking, but there’s no good mountain biking in town; you have to drive to all of it. What Breckenridge has is unique.”

Mills and his team of two have been working for 16 days on the park, but the persistent rain and sleet have left them three days behind schedule and up to their shins in muck. The Breck trail crew’s arrival in support of Elevated’s efforts means they just might finish the project on time.

Together the crew members take turns wrestling 150-pound boulders into place around culverts. They move logs. They clear brush. For hours and hours, without complaint. “There’s definitely a sense of ownership with this trail network,” Dukes says.

They work four 10-hour days per week, which allows for three-day weekends and more time to ride their bikes. “We get to go way out in the woods pretty much every day,” Muth says. “For a town trail crew? That’s rare.”

To place the job in context, at one point this morning Guild admits he has no idea how much he actually earns per hour—even after seven years on the crew. “Neither do I,” Walker says matter-of-factly. “I don’t think most of us do.”

“I doubt anyone’s over $15 an hour,” Muth says. “I’m probably around $13. That’s a safe average for this crew.”

“That’s how much we love this,” Dukes adds. “We don’t even care how much we get paid. We’re here.”

The crew’s heavy equipment specialist, Troy Heflin, helms a trackhoe

Image: Liam Doran

This summer, Overlock expects to open the new pump track and splice it into the town network; complete the long-in-the-works ZL Trail—a key connector from Breck to the Colorado Trail—as well as the Wire Patch Trail, which when complete will give cyclists a singletrack alternative to riding French Gulch Road; reroute a stunning alpine singletrack in Weber Gulch to make it more sustainable; and continue maintaining all the trails they already do. (A handful of local riders wish the crew spent more time on maintenance than new construction, but fielding such gripes is simply part of the occupation, Overlock says.)

Some of the construction will be aided by county staff (Summit employs a two-person trail crew), volunteers, and paid contractors, but the six-person Breck crew will be the backbone. As Overlock says, “We are constantly striving to make connections to the greater network.”

Their efforts are well funded and supported by various businesses in town. Breck itself allocates roughly $200,000—six times the budget of Park City, Utah, another ski town with a world-class singletrack network—to build and maintain trails, not including land acquisitions, and Reid expects that number to increase to $250,000 in the coming years if sales-tax revenue keeps pace.

As a result, gone are the days when Breckenridge’s crew counted four shovels and a beat-up Ford Explorer as their only inventory. Now they have a dump truck, a Vermeer trail mower, and enough Pulaskis, McLeods (wildfire raking tools), shovels, and implements to supply dozens of workers.

And while they appreciate any help they are afforded, you get the feeling they’d be perfectly happy if it were just the six of them out in the forest together: laboring, laughing, and leaving an imprint that will be there long after they are gone.

Builder’s Choice

We asked each member of Breck’s crew—all six are avid mountain bikers—to pick a favorite trail within the local network. As it happens, each selected a different stretch of singletrack. Here are their choices and rationale.

Tony Overlock (40, tenth year on crew):

I like the Wheeler. It’s the best above-tree-line trail around. Bombing down to Copper, or climbing the road from town then pedaling south and dropping into the Francie’s Cabin area—I love the adventure aspect. But for quick loops, I like Slalom and Barney Flow. There’s just more freedom to express yourself and ride how you want to ride the different features. To get there from town, climb the Peak 9 service road from Beaver Run until you hit the Wheeler junction, marked by a wooden signpost at 12,374 feet.

Nathan Guild

(41, seventh year on crew):

The Flumes. I try never to ride the exact same loop twice in a summer, but I live right next to the Flumes so I ride them a lot. I’ll ride Slalom to Middle Flume then up Mike’s, and I always finish with Upper Flume. We call that the Kennington Downhill, because it’s right next to the Kennington townhomes. To get there from town, start at the recycling center on County Road 450; the trail begins on the north side of the dirt lot.

Joel Dukes

(35, sixth year on crew):

Barney Ford. When I joined the crew seven or eight years ago, I always felt like that was our crown jewel. I like riding the armored switchbacks up top because I know how much work went into getting them there. To get there from town, climb the Carter Park switchbacks, then continue uphill on Moonstone.

Ryan Walker

(38, fifth year on crew):

Slalom. Now that there’s a clear cut through the forest, it’s not quite as sweet, but I like the flow and the speed of it; it’s fast and has some fun little moves with big berms. To get there from town, start at the recycling center and ride Upper Flume to Slalom.

Dominic Muth

(30, second year on crew):

V3. It has fun jumps and it’s kind of bermy, but it still has some rocky sections. I also like the ZL Trail, but I don’t consider it done [it’s slated to be completed this summer]. To get there from town, climb Carter Park to Moonstone to Barney Ford, then take a left on V3 halfway up Barney Ford.

Andrew Carney

(31, first year on crew):

Barney Flow. You can be a newer rider and just cruise down, or you can shred it and go as big as you want on all the gaps. I’m usually not a flow-trail person, but I like to connect it at the end of any ride I do. To get there from town, climb the Carter Park switchbacks, then continue uphill on Moonstone.