Heroes

Guardian Angels

For those who stumble onto death’s doorstep in Summit County’s rugged wilderness, salvation via Flight for Life’s air ambulance is just a phone call, and minutes, away.

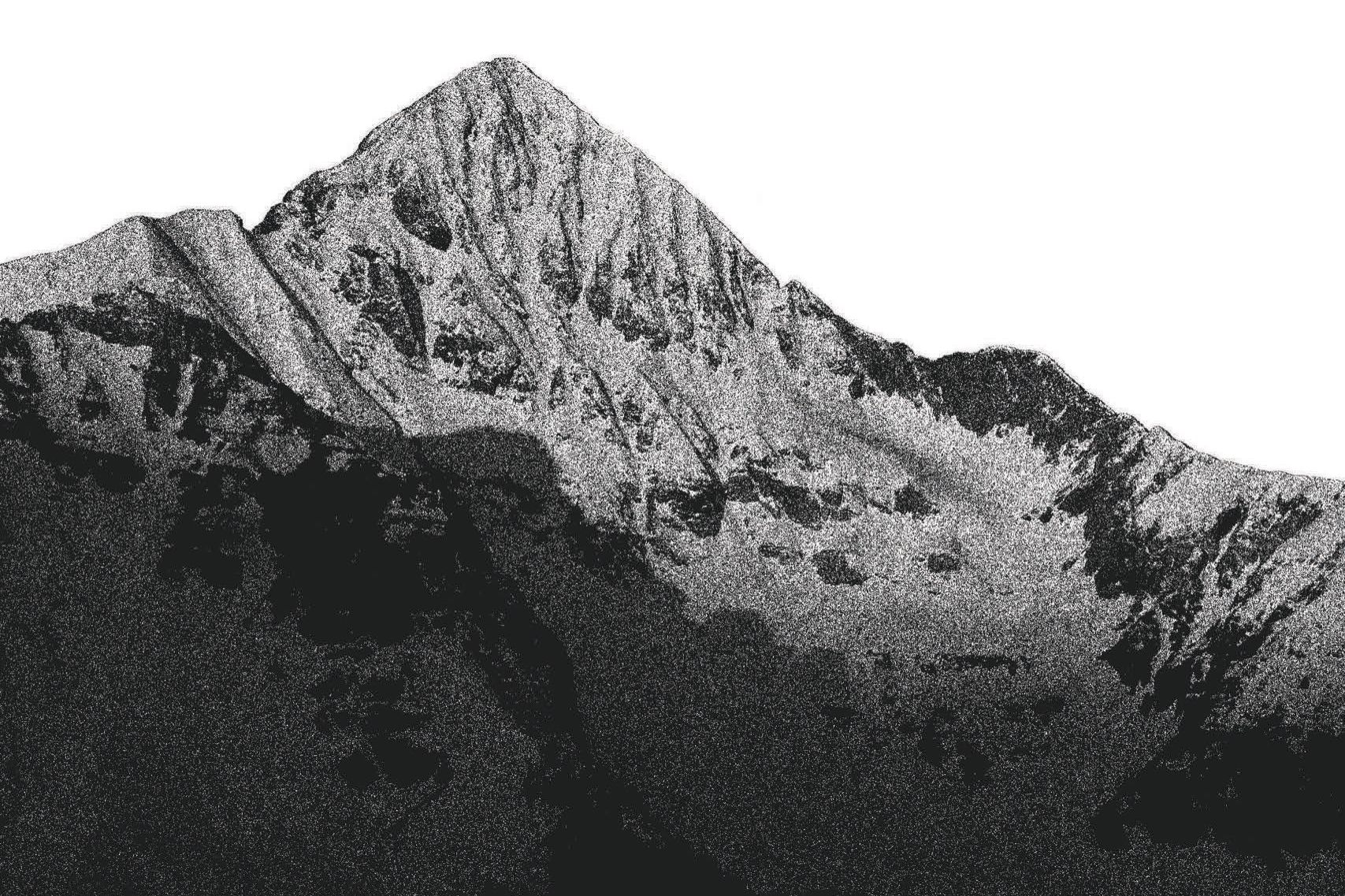

The telltale orange-and-yellow helicopter jerks to and fro like a hummingbird as it hangs between two giant snowy mountains. It is early June in Summit County: the heightened window of alpine possibility that separates spring from summer, when the snowpack solidifies and backcountry skiers test themselves on Colorado’s biggest lines. Flight for Life pilot Pat Mahany, who flew more than 900 hours of combat missions during the Vietnam War, keeps his eyes trained on the jagged rock surrounding his ship.

We are wedged in a gorge between 12,877-foot Buffalo Mountain and 13,189-foot Red Peak, just northwest of Silverthorne, high above a frozen waterfall. S-shaped tracks from recent alpine missions are visible in the cavernous Silver Couloir, which cleaves 2,500 feet down Buffalo’s north face and rates as one of the most famous ski descents in North America. Eight years ago, Mahany and his crewmate on today’s flight, veteran paramedic and avalanche forecaster Kevin Kelble, rescued a snowboarder who had been swallowed by a slab avalanche in the Silver Couloir and dragged through the rocky gauntlet that constitutes its lower half, barely surviving the trauma. Today, however, we are simply here to gape.

Suddenly the wind gusts, lifting the chopper up six feet, then immediately dropping it the same distance. My heart nearly punches through my chest. Mahany, 62, steadies the ship as the gusts start to swirl. I glance over at Kelble, who’s staring out the window at the craggy expanse.

Three nights earlier, a trio of skiers became cliffed out in the crater that drops off Buffalo’s east face, Kelble would tell me later. They were forced to spend the night above tree line, but Flight for Life probably would have airlifted rescuers to the scene had they called for help before dark.

Satisfied that all is well between Buffalo and Red, Mahany and Kelble decide via headset to leave the gorge and buzz one drainage north toward the Thorn, a piercing arrowhead that dominates the southern Gore Range. On the way, we pass a hawk scanning the ground for breakfast. “We can take a hawk through a windscreen,” Kelble shouts over the whirring rotors. “And that’s happened before with all of our helicopters. Hawks, ducks—they don’t want to hit you, either, but when you do hit them at 140 knots, they explode.”

Mount of the Holy Cross, Eagle County’s iconic fourteener, stares at us twenty miles to the west. In every direction below, pencil couloirs beckon up and down rock walls. To hike in and ski them would require a heavy pack and an enormous physical effort, at least one full day and maybe two. But if you injured yourself and had cell phone service, you could be plucked from the depths of the Gore Range and in 10 minutes arrive on the rooftop of St. Anthony Summit Medical Center in downtown Frisco, where Summit’s Flight for Life crew is based.

Senior flight medic Kevin Kelble has been flying with Flight for Life since 1981.

Flight for Life Colorado, a seven-station network of rescuers based around the state, is the oldest civilian air-medical program in the country. Its helicopters and ambulances (which are dispatched whenever the helicopter is grounded) transported around 4,000 patients in 2013, some 500 of whom were handled by the team of six flight nurses, four paramedics, and four pilots at Lifeguard 2, as the Frisco station is known. Think M*A*S*H, but with ski patrollers and mountaineers manning the ship. From plucking injured hikers off the summits of fourteeners to whisking sick grandparents with chest pain down to Denver, the range of helicopter missions that can begin on the concrete pad above the county library is equaled by few organizations in the world.

This is especially true in winter. With Kelble, 53, overseeing Flight for Life’s two most innovative rescue details, including the rapid avalanche deployment program that utilizes specially trained ski-area rescue dogs and snow techs, Lifeguard 2 covers most of the state’s avalanche accidents. Two years ago the station’s AS350 B3 became the first air-medical helicopter in Colorado to be equipped with a revolutionary, Swiss-made external avalanche beacon, which was introduced in the US by Wasatch Backcountry Rescue in Utah six years ago. The twenty-six-inch-long, three-antenna beacon dangles thirteen feet below the bird and can search for survivors 200 yards away—three times the range of a handheld beacon.

This winter, Lifeguard 5 in Durango will join Frisco’s station and deploy its own external beacon. At Lifeguard 2, the $3,000 instrument is stored in a yellow-and-black bumblebee case and will hang beneath a new helicopter this winter—the B3E (the “E” is for “Extended), which boasts 20 percent more power than its sister ship, which landed on the summit of Mount Everest in 2005.

The external beacon has saved many lives in Europe, according to Manuel Genswein, who helped develop the device and trains almost everyone who uses it, but it has yet to detect a buried person in Colorado. It could have been deployed this past April 20, when the deadliest avalanche in US history to involve skiers or snowboarders killed five men in Sheep Creek, just off of Highway 6 on the east side of Loveland Pass. Kelble was on duty that day and remembers hearing an initial, ultimately inaccurate report that ten people had been buried. He and other avalanche experts had long feared that a major slide would strike Loveland Pass and cause mass casualties. But on that day, sitting at his desk a five-minute flight from the scene, he was helpless: thick, milky snow squalls had grounded the helicopter. It turned out the external beacon wouldn’t have made a difference due to the close proximity of buried victims and the ease of foot access from the road—not to mention the four hours that had elapsed between the avalanche and rescue initiation.

For Kelble, that experience, however tragic and maddening because of his team’s inability to respond, provided yet another nugget of knowledge to be filed away. “I equate working in the backcountry, winter or summer, and avalanche decision-making to a chess game,” he says. “And when you think about chess players, the guys who win are the ones thinking five, six, seven moves ahead. The people who think one or even two moves ahead lose at chess. You have to consider: If I commit to this move, what’s my next move? And my next move, and my move after that?”

Flight for Life was founded in 1972 by a pair of physicians and the CEO of St. Anthony Hospital in Denver. After the 1976 Olympics were awarded to Colorado—but before voters would decide to veto that decision and send the Summer Games to Montreal—state officials instructed St. Anthony to develop an airborne medevac system for injured Olympic athletes who would require care in Denver. (Eisenhower Tunnel was still under construction, and Loveland Pass was a risky option for a number of reasons.) The hospital leased an Alouette from a pilot in Steamboat Springs, and the nation’s first airborne ICU was founded soon after.

The two-person crew—one pilot and one nurse—became a three-person crew in 1993 when Flight for Life added paramedics to the program, teaming prehospital experts with those accustomed to the hospital setting. Kelble, Lifeguard 2’s senior flight medic, had already been flying on an informal, volunteer basis in Frisco by the time the change was made: he had spent eighteen years forecasting avalanches for the Copper Mountain Ski Patrol and plugging stab wounds as a paramedic at Denver General, but in his spare time he was moonlighting as the unofficial flight medic.

“The fundamental belief of this program is to never, ever put financial considerations before the patient or the family or search-and-rescue,” Kelble says. “And that’s the no. 1 reason I work for this program.”

True to that mantra, Flight for Life provides about $5 million in uncompensated care each year—no small number for a nonprofit program with a $27 million budget. The disparity, according to program director Kathleen Mayer, is covered by base hospitals such as St. Anthony, with help from foundations. (Flight for Life also receives corporate and private donations in addition to patient payments, and donations from Colorado drivers who purchase Flight for Life license plates.) Helicopter-transport fees vary according to distance and the medical condition of the patient, but a flight from Frisco to Denver generally costs more than $15,000.

Ultimately, when it comes to backcountry rescues, Lifeguard 2’s primary mission is to provide air support for Summit County’s eighty-member, all-volunteer search-and-rescue squadron; members carry plastic orange Flight For Life “Lift Tickets” in their wallets, which are good for a one-way ride and stipulate that the “holder must have equipment and stamina to extricate themselves from the scene once they are dropped off.”

Even on a team stacked with backcountry know-how, Kelble, a diminutive 5-foot-7 and 145 pounds with slightly graying dark hair, stands out. He is a sought-after avalanche educator who has been known to teach a morning class in Durango, then drive 400 miles and teach a night class in Estes Park. He was (voluntarily) buried alive for thirty-five minutes as one of the first test subjects for the AvaLung, which helps avalanche victims breathe under the snow and survive up to three times longer than they otherwise would. Talking about air pockets and compression failures makes his face light up.

“Kevin has brought Lifeguard 2 and the avalanche deployment program up to worldwide standards,” says Mark Watson, a special operations technician with the sheriff’s office, who helps oversee the Summit County Rescue Group with special ops Sergeant Cale Osborn. “You’re looking at the cream of the crop out there. We demand a lot of guys who aren’t getting paid a dime—when they’re deployed, our expectations of them are very high.”

In working for Flight for Life, especially the station that covers the vast and rugged zone between Steamboat and Crested Butte, Kelble has catalogued plenty of stories from his missions. Some of them end well. Some of them do not.

One that ended well, as Kelble recounted on the helipad in Frisco, began halfway down the Silver Couloir on Buffalo in 2005. A group of four backcountry skiers and snowboarders were descending the chute that May when one ventured farther skier’s left and triggered a slide that raked him through an area that has killed at least three other people in different accidents. In this case, the victim survived his ride, but he was badly injured and in need of rapid evacuation. Kelble and Mahany tried six different landing zones near where the patient came to rest, but none was safe enough to use.

Finally, they found a level tuft of tundra a quarter-mile away. Mahany dropped off Kelble, then proceeded to shuttle search-and-rescue volunteers to help with the extraction. Because the entire chute hadn’t avalanched, conditions for a secondary slide were ripe, and Kelble and the other rescuers spent as little time in the strike zone as possible. They carried the victim to a safer spot, repackaged him, then loaded him into the helicopter for transport to Denver. He lived. It is uncertain whether he would have without the helicopter.

A much larger avalanche nearly two years later did not end well. In March 2007, three friends following directions in a guidebook snowmobiled up Independence Pass, then set out on climbing skins toward the top of Sunshine Peak, east of Aspen. Halfway up, the lead skier remotely triggered a massive slide across the peak, and he watched, awestruck, as an entire alpine bowl fractured, then slid. Initially, the skier’s own weight hadn’t been enough to release the unstable slope on which he and his friends had been skinning. Ten seconds later the shockwave from the first avalanche hit, and the skier and his two partners suddenly found themselves in the grasp of a secondary avalanche. The upper climber grabbed a tree and arrested his fall, but his buddies were carried 800 feet down the mountain and buried alive. The panicked skier did what everyone in trouble does: he called 911.

Kelble and Mahany were on duty at Lifeguard 2 in Frisco when Mountain Rescue Aspen, two counties away, requested their assistance. They found the accident scene using a topographical map and GPS coordinates, and Mahany dropped Kelble on a bench created by the debris. The survivor had located and dug down to his friends, and Kelble determined that both were deceased. Once the search and rescue team arrived on the scene, the operation became a recovery mission, adding to a grim personal toll: Kelble estimates he has recovered a dozen bodies in his career. More than hardening him—“I’ve realized that death is a consequence of people’s decisions”—the experience reinforced the most crucial lesson he has learned about snow: there is no such thing as certainty.

“I use that Sunshine Peak incident when I teach, because it really demonstrates how dynamic snow is,” Kelble says. “If you look at the photos, you’ll see that in between where his avalanche was and where the big slide in the bowl was, there’s a vast area over thirty degrees [in slope angle] that did not slide. So those two areas were able to communicate and not take out everything wall to wall. That’s just the mystery of snow. How in the world did this fail and this fail, but not this, and this, and this? I’ve seen it so many times in thirty years that I can’t even count.”

It is all a lot to consider as my stomach flutters a thousand feet off the snowy ground in the central Gore Range. Again Mahany steadies the chopper, now hovering next to a sawtooth ridge of spires. Kelble, gripping his seat, takes note. “Very few people can do what Pat was able to do here,” he says of Mahany’s ability to keep the bird steady amid whipping wind at an elevation of nearly 13,000 feet, an altitude where there’s precious little air to keep a rotary-wing aircraft aloft, much less properly oriented. “It’s one thing to have the right helicopter, but it doesn’t mean anything without the right pilot.”

At that, Mahany abandons the basin and points the helo back toward base. It is nearing 8 o’clock in the morning. He and Kelble, dressed in matching navy jumpsuits with shiny metal zippers and flame-resistant Nomex fabric, have been awake and working through the night. Their shift is almost up.

No sooner than ten minutes after we land, Mahany’s and Kelble’s replacements—including pilot John Peterson, who flew a Cobra gunship in Vietnam—are loading an elderly patient into the helicopter to take her down to Denver. The woman’s daughter and other family members have gathered on the windswept landing pad outside the hospital emergency room to see her off. They snap photographs with their smartphones as the flight crew secures her gurney to the deck of the cabin. When the B3 lifts off, with a thunderous roar and ferocious downdraft, the daughter seems to forget about her mother’s predicament for a moment and becomes transfixed by the whirring machine as it rises into the bluebird morning sky. “That’s power,” she says, awestruck.

For Kelble and his colleagues, as well as the thousands of patients whom they have flown to safety over the past forty-one years, it is life.