Living Here

Traffic Jam

What's to be done about ski country's expletive-inducing, gridlocked highway from hell?

Since the automobile arrived in Colorado, there have been three legendary traffic jams. The first was in 1900, when rancher William A. Bates took the state’s first horseless carriage for a test drive and confused his Autocar’s gas pedal with its foot-operated horn. The second was on January 8, 2014, when recreational pot shops opened in Denver and traffic citywide slowed to a mellow 4 m.p.h. And the third was on a Sunday a month later, when it snowed.

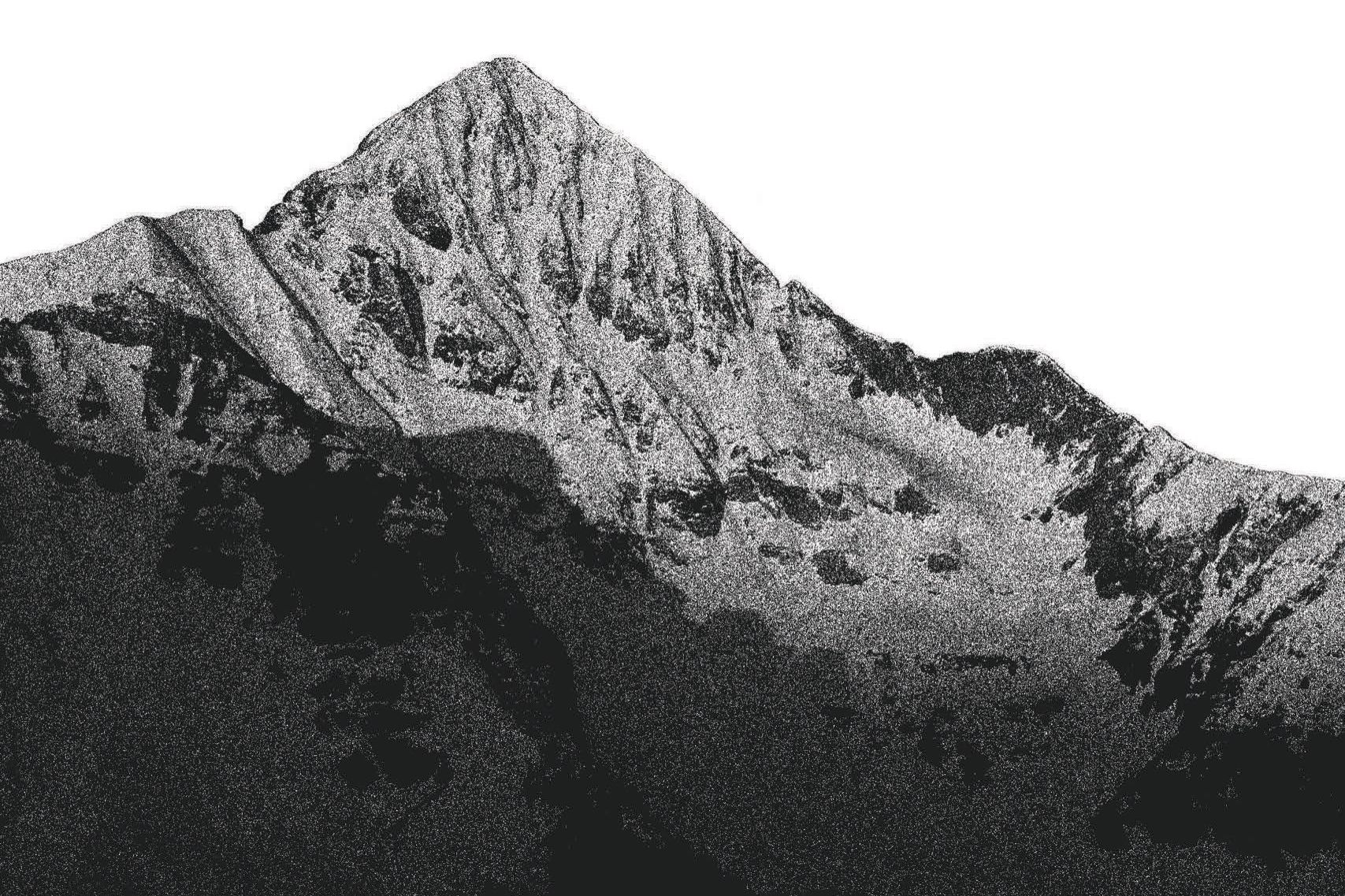

On February 9, 2014, the eastbound lanes of I-70 descending from high country resembled L.A.’s I-405 at rush hour, only with snow: as the storm intensified and tires started spinning, thousands of cars and trucks slowed, then stopped altogether. By evening, a string of bumper-to-bumper red taillights stretched for 58 miles from Vail all the way to Empire, and the normally one- or two-hour return commute from Eagle and Summit County ski resorts to Denver was taking some drivers the equivalent of an entire work day—no joke.

“It was hell,” says Jason Voerster, a Minneapolis mortgage broker who was one of thousands caught in the morass. “It was the worst I’ve ever seen, and I’m from Minnesota.”

According to the Colorado Department of Transportation, 56 vehicles spun out of control, and 11 semis stalled or jackknifed and needed to be towed. Cars with bald tires couldn’t get traction, so drivers would stop on steep grades and park. Some idled so long they ran out of gas. Voerster, stuck on I-70 for eight hours, entered “full survival mode,” as he puts it, and began rationing trail mix and water. He fell asleep for a full hour, and when he woke up the car in front of him hadn’t moved. Voerster’s return flight from DIA left without him, so he rented a hotel room and rebooked his plane ticket—which cost him $500 and ultimately, because he missed a Monday morning meeting, a sales opportunity. Factoring in that lost commission, the ultimate toll Voerster paid on I-70 that fateful night tallied in the thousands.

After skiing Telluride that day, Pennsylvanian Larry Belluchie spent seven hours inching his way from Avon to Georgetown, white-knuckling the steering wheel until his nerves were frazzled. “I was raised in Glenwood, and that’s the worst I ever saw,” he says, adding that he’ll never drive I-70 to Denver on a Sunday again: “I don’t know how Denverites put up with that.”

Many don’t. A Denver skier named Kathleen McCarron is not alone when she notes that she hasn’t purchased a ski pass in three years because of the traffic on I-70. Lost lift-ticket revenue aside, one study estimates that I-70 traffic jams are costing the state $85 million in time wasted by workers who could be doing something more productive than idling behind a steering wheel.

It’s anybody’s guess as to how many—if any—out-of-state skiers are opting to spend their vacations in Utah or Idaho instead of Colorado because of I-70’s storied traffic jams, but as the main link between the state’s population center and many of the country’s busiest ski areas (not to mention freight destinations to the west), the I-70 mountain corridor remains one of the state’s most important stretches of road. The scrunch of February 9, one of many instances in which the artery has become unhealthily and dangerously clogged, had at least two positive consequences. It catalyzed state and local officials to immediately reassess how traffic is managed from Denver through the high country, and it prompted politicians and regular folks to consider a very fundamental question: what can be done about I-70?

For decades, Coloradans and visitors have dreamed of a train that would effortlessly whisk them to their ski vacations like the Eurostar Ski Train, which offers direct overnight service on weekends from London to Moutiers and the slopes of Les Trois Vallées, one of the European resorts that honor Vail Resorts’ Epic Pass. The Colorado Department of Transportation spent two years studying the possibility and found that, technically, a high-speed ski train is doable. A maglev train, lifted and propelled by powerful magnets, could climb the steep grades in the mountains while reaching speeds of 150 or even 180 mph, delivering skiers from Golden to Breckenridge in a half hour—and bypassing traffic jams.

The department’s rail guru, David Krutsinger, says that building such a train could have far-reaching ancillary benefits. In addition to making slopes more accessible to Front Rangers, a high-speed ski train would make Summit’s ski towns more pedestrian-friendly, with fewer out-of-town cars tootling about. And it could reduce ski-town sprawl, since fewer Front Range skiers would feel a need to build expensive second homes here to curtail their back-and-forth trips.

What’s more, Krutsinger adds, the timing seems right for a high-speed ski train. The Front Range’s population is expected to swell by 52 percent by 2040, which means 1.3 million potential new skiers on the slopes. Many of those arrivistes will be millennials who tend to be more interested in texting than steering, increasing the appeal of a rail connection. Also, many of those text-happy millennials adhere to environmentalist values that would be catered to by a solar-powered ski train’s reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. And last but not least, those reductions in greenhouse gas emissions might help forestall the effects of climate change, which, as Coloradans can attest with their own eyes, has already made the local ski season a month shorter (by one estimate) than it was 50 years ago. In other words: if not now, when?

The high-speed ski train’s Achilles’ heel, of course, is its projected cost: more than $16 billion for a line from Denver to the Eagle County airport, an astronomical (and some would argue unjustifiable) sum given that CDOT’s entire annual budget, for the whole state, is $1.2 billion. The state could more than halve that tab by starting small and building a line from Golden to Breckenridge that would cost nearly $7 billion, roughly the cost of Denver’s new FasTracks system, which includes six new light-rail lines carrying riders all around the metro area.

“We’re going to have to make hard choices if we want to keep giving us access to the great outdoors without eroding it by paving it over,” says Krutsinger. “If we can’t ski and hike and fish, we might as well live in Nebraska.”

But paying for it is the challenge, given that the federal highway fund (which includes funding for mass transit projects like FasTracks) is nearly insolvent, and revenues from the gas tax (which hasn’t been increased since 1993) are declining as cars get increasingly better mileage.

Coloradans could simply tax themselves and tourists, and it wouldn’t take much: a half-cent increase in the state’s sales tax could raise $3.5 billion over 30 years, enough to build the Golden to Breckenridge line (if the federal government matches that amount). But does Colorado have the appetite for higher taxes? Perhaps yes: the Denver metro area did vote for a tax increase in 2004 to fund FasTracks. Perhaps no: when Coloradans statewide were polled a year ago to ask whether they would support a sales tax increase to fund infrastructure improvements, there was little support. The idea died.

Statewide, Coloradans aren’t exactly known to embrace public transport. And it’s worth noting that until recently Colorado had a ski train, between Denver and Winter Park. Although it was much slower than the high-speed train CDOT envisions and served only a singe resort, it did coax thousands of skiers out of their cars and onto the rails on their way to the slopes. Yet it screeched to a halt five seasons ago after losing money for two straight decades: not enough people rode it.

With upfront funding unlikely and ongoing solvency unassured, a high-speed ski train seems a distant dream.

“Colorado probably will not be the first in the nation” to undertake such a project, says Tony DeVito, a regional transportation director at CDOT.

So what else can be done?

Certainly, the highway could be widened, from three or six lanes up to eight or even ten, as many drivers are incessantly demanding. There are hurdles there, too, including the cost. Adding a new lane in each direction from Golden to Silverthorne would cost an estimated $4 billion to $5 billion, nearly as much as our maglev pipe dream. Tolling the new lanes would help pay for the project, but an additional $1 billion from other sources (again, nearly CDOT’s annual budget for the entire state) would probably still be required.

And any CDOT traffic analyst will tell you that simply adding more traffic lanes to existing clogged roadways isn’t a viable long-term solution. There’s a pattern: a highway gets jammed; construction crews spend years (and the state spends billions) widening it; then, after a brief period of improved traffic flow, the new wider road again jams up with cars, and it’s time to widen the road again. That’s actually doable on the flat Eastern Plains (or in Phoenix), if residents accept the trade-off of convenience with the consequence of sprawl. But in the high country, mountains stand in the way. And though most Coloradans do want to get to the slopes faster, it’s not clear how wide of a river of asphalt they want to see sullying the majesty of an alpine vista, or how many shoulders of how many mountain passes they are willing to see blasted to smithereens. After all, the mountains are the reason they’re driving up this way in such numbers to begin with.

So Coloradans find themselves in, if you will, a jam—without money (or the will to raise it) for a train, and with a limited appetite for endlessly widening the road. It’s a recipe for frustration. After the February 9 storm, drivers ranted on the transportation department’s Facebook page: “you fail,” “ridiculous,” “morons.” One skier used the word “brilliant,” but he was being sarcastic.

“A vocal minority always wants simple solutions to complex problems, and as a result we get both political and traffic gridlock,” said says Chris Romer, a former state senator who has worked on the I-70 problem extensively. “Solving complex issues like I-70 requires more listening to each other, studying the data, and less shouting one’s beliefs.”

To that end, instead of spinning its wheels lobbying exclusively for one big, expensive (and perhaps unattainable) long-term solution like maglev, the state’s transportation department is championing dozens of less ambitious (and more affordable/attainable) traffic-busting initiatives designed to yield immediate results.

The most dramatic and innovative fix happening now is a project CDOT dubs “peak period shoulder lane.” On the eastbound half of the interstate in the area around Idaho Springs, the highway’s shoulder is being widened and strengthened to create a third lane, which drivers who pay a toll will be able to use to zip by stalled traffic during periods of heavy use. Once the peak period shoulder lane opens in fall 2015, when combined with the newly expanded Twin Tunnels (scheduled to open on December 20), on Sunday afternoons eastbound I-70 will stretch a supersized three lanes wide from Empire Junction all the way to Denver. The department expects the changes to shave 30 minutes off travel time between the Eisenhower Tunnel and Floyd Hill.

Meanwhile, the transportation department is working harder to regulate the flow of traffic. Beginning this ski season, a just-hired mountain corridor operations manager, stationed at the Eisenhower Tunnel in a new operations control center, will oversee a staff of six, including dispatchers, maintenance managers, and ultimately a state patrol liaison officer. Managing the highway like air traffic controllers, this crew will monitor cameras offering a view of most of the corridor (enabling them to summon state patrollers to respond to any accident or traffic-clogging incident) and communicate with drivers via electronic reader boards along the highway (alerting them of closures or delays ahead). In addition, stoplights that have recently been installed at the on-ramps at Copper, Frisco, Silverthorne, U.S. 40, and U.S. 6 will ease traffic onto the highway at a predictable clip. During storms, snowplows will act as escorts, driving two, three, or four trucks abreast and setting a slower pace for traffic, and Western Towing has contracted to tow stalled or stuck vehicles to a safe place, free of charge to the vehicle owner.

“I do not think that we will have the severity again like we had on February 9,” says Patrick Chavez, the new mountain corridor operations manager, who recently retired from a career in the military. “There’s always going to be congestion, but we can manage that congestion to get it to the lowest level possible.”

But it’s largely an exercise in futility unless the department can convince irresponsible drivers who frequent the roadway to recognize and accept that they contribute to the problem. On February 9, of the 22 passenger vehicles the CDOT moved off the highway, 19 had bald tires. In other words, it wasn’t just the conditions; it was the cars. (And before locals start ranting about how Texans and Californians need to learn how to drive in the snow, note: 18 of those vehicles had Colorado plates.) So in the fall, reader boards from Denver to Glenwood Springs flashed, “Winter is coming. Are your tires ready?” And throughout ski season, volunteers will check tires in ski-area lots and leaflet windshields with flyers warning about the danger of driving with bald tires, along with coupons offering drivers incentives to buy new ones. CDOT, with the I-70 Coalition (a consortium of local governments and businesses along the I-70 mountain corridor), also is sponsoring a new publicity campaign called Change Your Peak Time (goi70.com), urging skiers to leave the resorts by noon on Sunday or delay their trip home until after 8 or 9 p.m., when there isn’t usually much congestion; hotels and restaurants along the highway are offering discounts and incentives to lure drivers off the road.

So far, it does seem like the message has gotten out—to the point that drivers are criticizing this move, too. “The suggestion to have travelers go before 1 and after 7 was the dumbest idea ever,” one wrote on the department’s Facebook page. “’Cause every single person has decided to do this.” Another added: “Nobody drives I-70 during rush hour anymore. IT’S TOO CROWDED!”

Even moves meant to smooth traffic seem to illustrate the point that there is no easy way out of this mess. But some drivers, such as Evergreen’s Nora Pykkonen, are modeling inspirational traffic-busting alternatives.

By 2012, Pykkonen, the founder of a successful consulting firm, had been spending hundreds of hours stuck behind the wheel of her white Suburban, ferrying her three school-age daughters (Riza, Falyn, and Kaylie, then 9, 11, and 14, respectively) to ski-race practices in Vail. When the girls ran out of homework to do, they watched The Princess Bride until their mother could practically recite every line in the movie by memory (“No more rhymes now, and I mean it!” ... “Anybody want a peanut?”). Pykkonen tried changing her drive time and tried carpooling. It wasn’t enough.

Taking advantage of a tantalizing business opportunity, she made a dramatic move: Pykkonen sold her second home in Vail, raided her retirement and the kids’ college funds, put a coda on her consulting career, and bought a ski resort.

She owns the old Echo Mountain, now the Front Range Ski Club, a members-only facility dedicated to ski racing. Every day, Pykkonen’s dealing with weather, snow-making equipment, and finances, a much, much harder job than running a consulting firm, she says. But at least she’s not sitting in traffic on I-70. csm