Backcountry

Full Moon Fever

Under nature’s disco ball, backcountry revelers party on Loveland Pass.

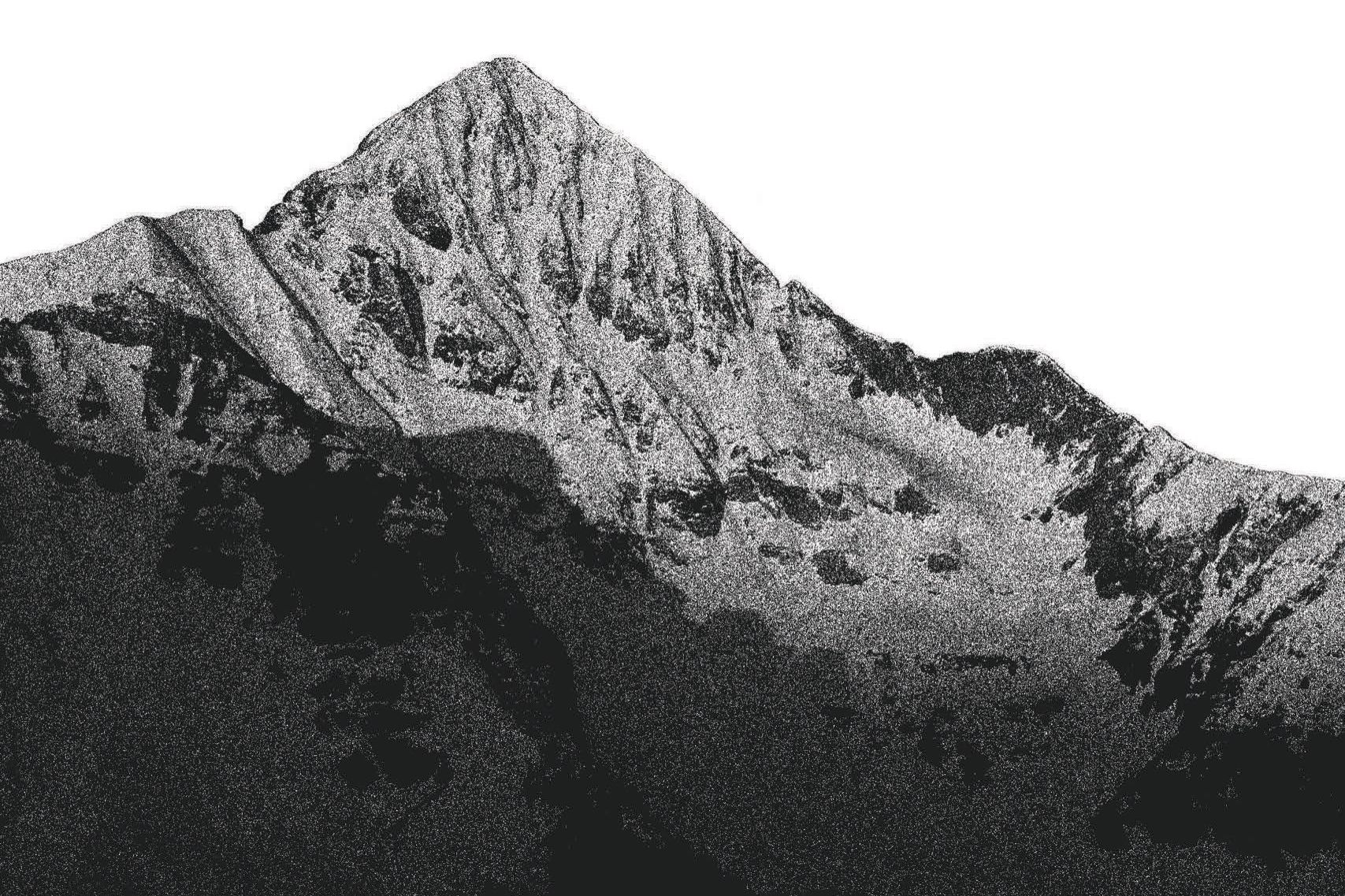

When we pulled into our parking space at the summit of Loveland Pass, the full moon was barely visible—but the pass was buzzing. It was March 2003, and my brother and I had driven over from Breckenridge to join what we’d heard was a rousing monthly party. Some people hung out next to their trucks or campers, nursing beers and laughing as the flakes floated down from the sky. Others trudged off the pass’s north side, skis and boards strapped to their packs, about to drop in for a powder run at 10 p.m. Still others arrived by the dozen in the back of a pickup, shuttled up for another lap by a rotating cast of designated drivers.

We began to gather our gear for what would be the first backcountry ski run of my life. I wondered what awaited us below. A friend had said the party was not so much on top of the pass as in the trees near a parking area two miles down the east side. All we had to do was get there.

We clicked into our bindings, scouted our route by the glow of the moon, and began skiing downhill by headlamp, silently but for our skis’ slicing through the untracked snow. While picking my way through the forest, I saw a new glow ahead and skied toward it. Suddenly the trees gave way to a wide clearing and a ten-foot-tall bonfire, fueled by wooden pallets and surrounded by 100 people in ski and snowboard gear. I cracked one of the beers in my pack, found my brother, and took a place next to the fire.

Over the course of our hourlong stay, we watched various revelers huck themselves over the fire pit to boisterous cheers. With attendees coming from both Clear Creek and Summit counties, I got the feeling that everyone knew someone, but no one knew everyone. Eventually we skied down 100 yards to the road, stuck out our thumbs, and caught a ride back up for a second run.

It’s hard to say how long Loveland Pass has played host to full-moon parties. Decades, to be sure. The tradition involves some level of risk (the pass’s steeper slopes are prone to avalanche in the wrong conditions) and has in the past rankled local law enforcement officials, who field complaints from hazmat drivers angry that they have to snake around cars picking up people on the side of the road on what is a tricky drive as it is. Despite those factors, even now that I’ve cut back on my full-moon ski runs, I take solace in knowing that the party on the pass still offers something wild and different: night skiing en masse at 12,000 feet. You can’t find that just anywhere.

Get there: Park at the top of Loveland Pass, shoulder a pack containing backcountry survival essentials (including avalanche beacon, probe, and snow shovel), and chart an east-northeast route on lower-angled slopes to the creek bed until you reach the bonfire or the road, then hitch back up for another run.

Alternate party: Hoosier Pass

Playing It Safe

Although levels of avalanche know-how range from plebe to guru, the most valuable safety tips are often the most basic. For starters, never go alone. Always carry a transceiver, a shovel, and a probe (and, for good measure, an airbag—see opposite page), and practice using them before you enter avalanche terrain, which generally means slopes steeper than twenty-five degrees. Be accustomed to recognizing dangerous terrain features, like convex rollovers (a stress point at the top of a steep slope that can fracture and trigger a slide), as well as safe zones on suspect slopes, like ridgetops. Learn to read the messages a snowpack is sending—shooting cracks or “whumpfing” sounds, for instance, mean the snow is unstable.

“You really have to change your paradigm when you’re backcountry skiing,” says longtime avalanche forecaster and Blue River resident Scott Toepfer. “You don’t necessarily look for reasons to ski something; you should be looking for reasons not to ski something.”