Panorama

It’s a Gaz

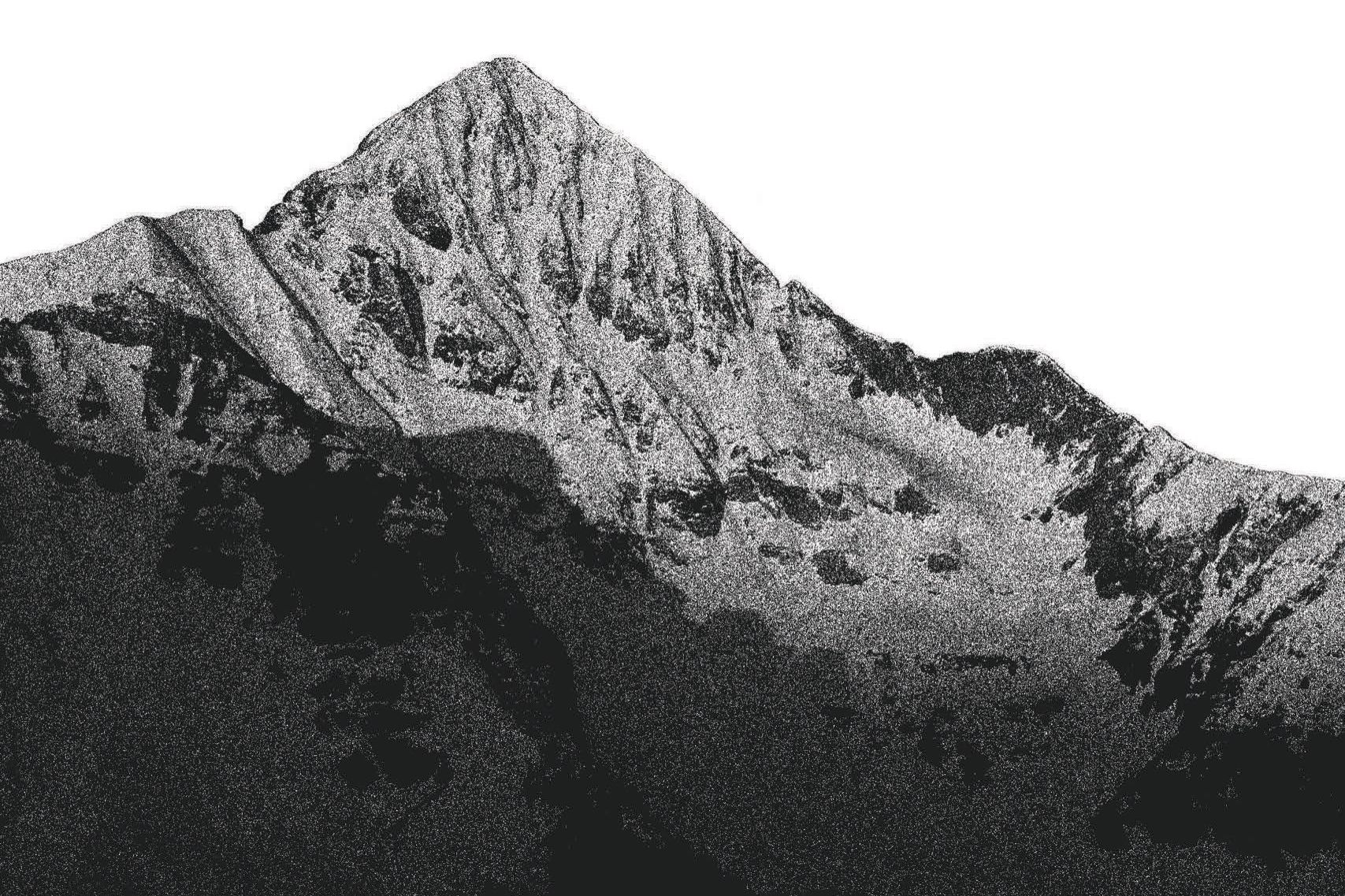

Cannons from the French Alps keep motorists—and state workers—safe from avalanches on Loveland Pass.

Image: Liam Doran

Just before dawn on March 31, 2014, two state workers conducting an avalanche-mitigation mission on the east side of Loveland Pass were seriously injured by an explosion. The men were using a cannon-like gun called an Avalauncher to fire live ordnance onto the hillside just east of Loveland Ski Area, into a zone known as the Seven Sisters due to its seven distinct avalanche paths. One of the charges detonated while it was still in the Avalauncher’s barrel, maiming the men.

The accident helped spur the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), which employed one of the injured duo (the other worked for the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, or CAIC), to invest in a new, safer way of conducting avalanche mitigation above Highway 6, which brings droves of tourists to Summit each winter. The system is called Gazex, and CDOT already had plans to install it on Berthoud Pass when the accident occurred at Loveland. The Sisters presented a logical case of their own, with huge gains possible in safety, efficiency, and bottom line (after absorbing the $2.5 million price tag). In October 2015, CDOT installed 11 Gazex “exploders” throughout the Seven Sisters: remotely detonated, tube-like cylinders where a mix of compressed oxygen and propane deliver a concussive blast that shakes the valley and helps the paths shed any suspect snow.

CDOT and the CAIC spent much of last winter learning the system, but the advantages were immediately clear. Fifty-seven percent of their blasts produced avalanches—which is, of course, the goal—compared with just 25 percent of Avalauncher shots, which are more expensive and more dangerous. Operating cost was the lowest in five years, due in part to a 90 percent reduction in man-hours, as prep time in the frigid chill of dawn was reduced from an hour to 10 minutes. In addition, because the system can be remotely detonated, CDOT rarely has to close the close the two-lane highway between the Interstate 70 exits and Loveland Ski Area, a boon to skiers and hazmat trucks needing to bypass Eisenhower Tunnel.

“Mostly what we’re seeing is it’s a lot easier to do the work that we do,” CAIC Director Ethan Greene says while peering up at the exploders in October, 100 yards south of the 2014 accident site. “But we’re only one season into it, so we’re sort of still in the honeymoon phase.”

A Gazex exploder similar to CDOT’s new Loveland Pass avalanche mitigation system protects backcountry riders in the French Alps.

Image: Liam Doran

The system, made by a company based in the French Alps, works like this: an avalanche control technician situated at the I-70 off-ramp just south of Loveland Basin powers up a laptop at first light, then pushes a button to tell the Gazex computer, high on the ridge a half-mile away, to start sending oxygen through an under- or aboveground gas line into the chosen exploder. The propane follows, and when enough propane reaches the valve at the end, a pair of spark plugs automatically ignite the gases, producing a percussive blast. The entire process takes about two minutes for each exploder.

Gazex is popular in Europe, Canada, Central Asia, and South America, but it is still catching on in the United States. Only Wolf Creek Ski Area in southern Colorado and Utah’s Brighton use it to control their in-bounds runs. It is also used to mitigate slides in Little Cottonwood Canyon, home to Alta and Snowbird, and on Teton Pass near Jackson Hole. On Loveland Pass, Greene says, they hope to optimize exploder blasts to compress the time requirement even further, and someday possibly use it at night if a major storm warrants multiple missions per day.

CDOT engineer Tyler Weldon sums up the advantages this way: “When you increase the effectiveness and you increase the occurrence of the avalanches, they’re going to be smaller,” Weldon says. “Then, theoretically, there’ll be less snow on the highway.” And everyone loves an open road in winter.