Heroes

Helping Hands

Summit’s top docs take their skills to remote regions of the world to help those in need.

Patti and Peter Janes at St. Anthony Summit Medical Center

For most people, donating their time and expertise is local, personal, and relatively convenient. Journalists help students proofread their papers; professional skiers make turns with a city kid; a plumber shows his buddy how to stop a leak in the sink.

For medical professionals with highly specialized skills, by contrast, volunteering can be a logistical and emotional quagmire that involves travel to some of the planet’s most isolated and hopeless places, not to mention only fleeting interaction with the communities they are trying to help. But it can save lives—or, at a minimum, drastically improve them.

Medical missionaries, as they are known, do not covet attention. In fact, if the interviewees for this article are at all representative, they shun it. Their contributions are too small on the grand scale to be highlighted, they say, which is a fair point. But these dedicated volunteers also see life through an unpolished prism, spending their time in places where actions matter, survival is the goal, and the perspective gained in a single day can totally alter anyone’s worldview.

Summit County is home to a number of such people, men and women who often risk their safety to help human beings they have never met and sometimes will never see again. They pay their own way and bring hundreds of pounds of supplies. To call them medical missionaries is to lump them in with tens of thousands of like-minded doctors and nurses and anesthesiologists around the world, which is fine by them. But since each one has stories to tell and perspectives to share, we chose to spotlight four and let their experiences speak for the rest of these quiet heroes.

Two Specks of Sand

In 2005, Breckenridge residents Peter and Patti Janes traveled to rural Uganda with their three kids, then aged 15 to 21, to hack trenches to bring water closer to the local village. They did so at the request of a friend of theirs in Denver, a Ugandan minister—it was his village, and his people needed help.

The Janeses toured three hospitals in Fort Portal, and Peter, an orthopedic surgeon with Vail Summit Orthopaedics, couldn’t help but notice the vast medical needs of area residents, including a tiny boy with a clubfoot. Normally the boy would have been doomed in the rural area, but Peter knew to put a cast on his foot, improving his chances. From then on, he asserts, “I decided my experience and training would be better used in a surgical setting than getting blisters on my hands digging ditches.”

Patti Janes, a registered surgical scrub nurse at St. Anthony Summit Medical Center, has teamed with her husband on a number of missions since, but those collaborations are only a fraction of the trips she’s taken. She’s been to Africa 5 times and Honduras 19; on her latest Honduras trip, she was the most qualified medic on a team that treated people in 18 villages and taught indigenous residents how to administer first aid. The final mission she took last fall was her sixth of the year, including three to Honduras, two to Rwanda, and one to earthquake-ravaged Haiti. (Peter joined her for one of the Rwanda trips and the mission to Haiti.)

“The trips are both rewarding and frustrating, because you can’t help everybody,” Patti explains. In Rwanda, they treated a month-old femur fracture and a boy whose radius bone had been sticking out of his skin for a year. They also spoke with a hospital worker who lives among the same people who murdered his wife and children during the genocide, when 10,000 people a day were killed for three months straight.

“They tell me, and I find it hard to believe, that they have two orthopedic surgeons for 10 million people in Rwanda,” Peter says. “We have 20 for two counties.”

On another trip, in 2007, the Janeses flew to Tanzania to volunteer at a 400-bed Norwegian hospital in the middle of nowhere. While they were there, a rabid hyena attacked four villagers. An old goatherd had his eye ripped out, a testicle bitten off, and lost both thumbs and three other fingers while trying to protect his animals. A 12-year-old girl was walking to school when the hyena bit through her skull and ripped off the left side of her face. Both survived.

“Those kinds of things stick with you,” Peter says. When asked what she takes from such experiences, Patti replies, “That I’m a tiny little speck of sand touching another speck of sand and making that one person’s life better for one day.”

The Janeses, who spent nine years in neighboring Eagle County before moving to Summit in 1995, have been married for 27 years. “We met over a woman’s gall bladder in the operating room,” Peter remembers. “All I could see were her eyes.” And the couple’s inclination to volunteerism has been with them from the start. Peter’s father, a World War II surgeon who worked at the Mayo Clinic for 30 years and once served as team doctor for the U.S. Olympic hockey team, always emphasized humanitarian principles.

“My father brought me up to give back to my community,” Peter says. “And I suppose my community has become more than just local. We help a few people for a short time—we’re not saving Africa or saving Haiti.” After a pause, he adds, “I always feel like I should stay longer and do more.”

Last year, the Janeses brought their service ethos home by helping to spearhead the inaugural free surgery day in Summit County, a joint operation between Peak One Surgery Center and the Community Care Clinic—an idea they conceived while in Haiti, treating three-week-old open fractures. Roughly 75 people volunteered on a Saturday, performing 14 procedures.

“People sometimes say, ‘Oh, I could never do what you do,’” Patti Janes reflects. “But there’s nothing more important than your time and your touch. You don’t need a skill. Just your time and your touch. Even the people who have nothing, they’re all helping each other.”

The Jungle Doctor

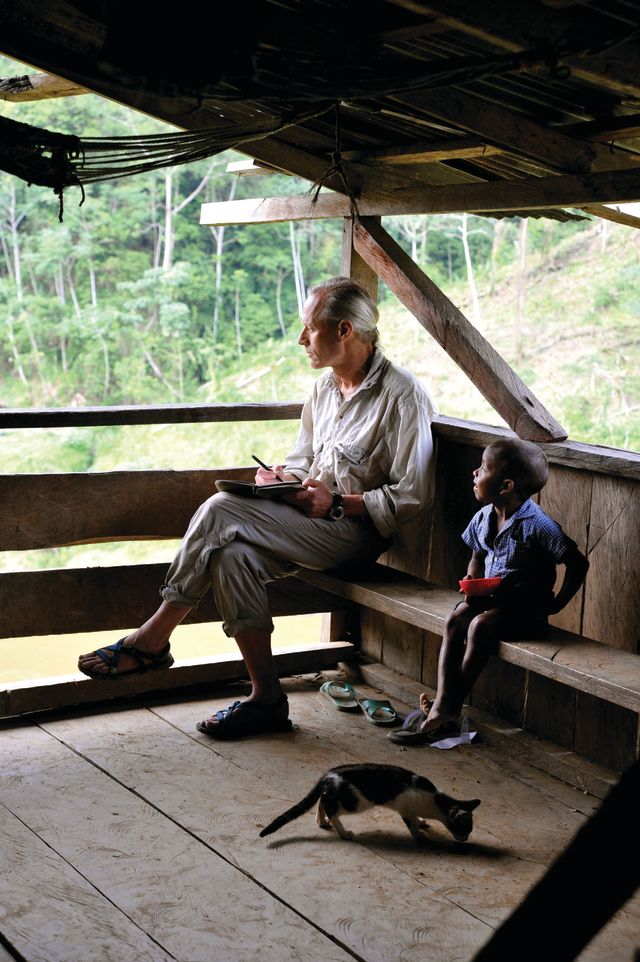

High Country Health Care’s C. Louis Perrinjaquet

Image: Dr. C. Louis Perrinjaquet

A long time ago, Dr. C. Louis Perrinjaquet spent a summer as Michael Jackson’s personal physician. That may explain why nothing fazes him—not running trail marathons at 12,500 feet in homemade sandals, not pulling maggots out of a wounded leg in Haiti, not occupying his frigid house in the middle of winter. He rarely turns on the heat or drives a car.

Doc PJ, as he is known, got involved with volunteering early. He worked at a free clinic during medical school, then donated his time on Indian reservations, and worked at free clinics in a number of other cities before settling in Breckenridge in the late 1980s. Here, he donated his services to the old free clinic off of Frisco’s Main Street, and in 1991 he orchestrated his first international mission: to Vanuatu in the South Pacific. “It just feels like the right thing to do,” Doc PJ says of volunteering. “I’ve always been drawn to serve the underserved.”

Since 1991, the 56-year-old has made 30 trips to 13 countries, including his fifth trip to Nepal this past autumn. There, he met up with an old friend whom he had put through medical school. Together, they traveled through the Langtang District—where Doc PJ had donated $30,000 for a clinic to be built—and treated 7,000 people in a little less than 30 days. He has worked in Sudan’s war-torn Darfur region during a raging gun battle, fallen off of a cliff in Honduras, and practiced medicine by the light of a single bulb on a remote South Pacific island that he reached via a plane that landed on a sandbar. The locals there called him Bigfela Witeman Docta. “They would kind of sing it,” he chuckles.

In all, Doc PJ undertook three medical missions overseas this year, his most ever. “My mission is just to help people be more self-sufficient and healthy,” he explains. In Honduras, he has provided health care for years to 4,000 people in Patuca National Park and to more than 1,000 on the Tawaca Indian Reservation, home to a dwindling ethnic group. Since he doesn’t like bureaucracy, Doc PJ always opts to do his work in rural areas. He practices transcendental meditation—and nearly got killed while doing so in an Iranian hotel, after locals suspected him of being a foreign journalist. He and his friends were marched outside and assembled for a firing squad before someone vouched that they weren’t journalists.

Despite all of these experiences, when he got to Haiti in the wake of the 2010 quake Doc PJ was astonished. “That trumps everything in terms of intensity and severity of illnesses,” he reports. “Everywhere you go, there will be one or two people who are really sick. But in Haiti, everyone was really sick.”

Doc PJ spends about half of his income funding his missions, but it could be more. His nonprofit, Doctors to the World, generates unsolicited donations that aid in his efforts; one year he accepted nearly $50,000. (Usually it arrives in $50 or $100 checks.) And he relies on two of his fellow doctors at High Country Health Care to cover for his absences—he knows he couldn’t hold a job and also leave three times a year if not for them.

He also understands that he won’t be able to do this forever. But when he’s forced to slow down, he says, “I’ll just have to work in areas that are a little more accessible.”

Home Again

Matthew Cowell

You’d have a tough time finding a more versatile or hardened medical missionary than certified registered nurse anesthetist Matthew Cowell. A Colorado native, Cowell, 49, grew up in Golden and joined the Lookout Mountain Fire Department when he was 16. He became an emergency medical technician (EMT) and then, at 18, the youngest paramedic in Colorado. He liked helping people, but felt that there was a ceiling involved with being a paramedic.

So he went to nursing school, then joined the army at 25. The army put Cowell through its nurse anesthesiology program, after which he served in Haiti, Germany, Korea, and Alaska, among other locales. To supplement his work and make use of his skills among people who needed him, he began volunteering for Operation Smile, a worldwide organization that fixes cleft lips and palates on otherwise helpless children.

“These kids are shunned from school and from the other kids,” Cowell notes. “Their mothers love them, but the country doesn’t love them.”

With Operation Smile, Cowell typically took two weeks off annually and paid for supplies and his own travel costs in countries such as Ecuador, Colombia, El Salvador, and Guatemala. During his visits, he’d often help complete 15 to 20 surgeries.

Seeing the children’s faces light up when their deformity was fixed brought him immediate gratification.

After a decade of Operation Smile missions, Cowell was deployed to Iraq in 2003 and no longer had time for medical missions. He was stationed at Ibn Sina, the world’s busiest trauma hospital in downtown Baghdad, which had been Saddam Hussein’s personal hospital until he was overthrown. “I saw stuff there that I never thought I’d see in my life,” Cowell reveals.

One night, two Humvees carrying four soldiers apiece stopped over a roadside bomb that they never saw. “Two guys died in the blast, and they brought the other six to the hospital,” Cowell remembers. “Out of six people, we saved one leg. And that took all night. It just blew me away how quickly so many people can lose their legs.”

Cowell returned to Colorado in 2006 after two tours and more than 700 days in Iraq. He retired as a lieutenant colonel in 2007, and in March 2008 took a job at St. Anthony Summit Medical Center. That’s where he met the Janeses. Now, the three constitute a complete surgical team that has worked together on missions in Haiti and Rwanda this year. The needs are particularly poignant in Rwanda. “They’re using drugs that were common for us in the 1960s,” according to Cowell. “They kill a couple of people a month under anesthesia. It’s important for me to educate them about a better way, a safer way.”

He wants to continue the missions at least once a year. “We in the U.S. have a ton of resources, whether financial, educational, or medical,” Cowell says. “For me, I just like to take those and give them to someone else.”

Spoken like a true Summit County medical missionary, for whom the work is never done.

Breckenridge resident Devon O’Neil is a contributing writer for ESPN.com and freelances for publications ranging from Outside to O: The Oprah Magazine.