Bicycling

Breaking Away

When the USA Pro Challenge's peloton rolls into Breckenridge in August, the world will be watching. Could this be America's Tour de France, or is a rerun of the Coors Classic?

The USA Pro Challenge, a slickly produced road race that’s lured the world’s top two-wheeled talent and thousands of cycling fans high into the Rockies the past two summers, spins into its third edition this August. Can the race achieve ascendancy as America’s Tour de France, or will it coast into obscurity like the bygone Coors Classic?

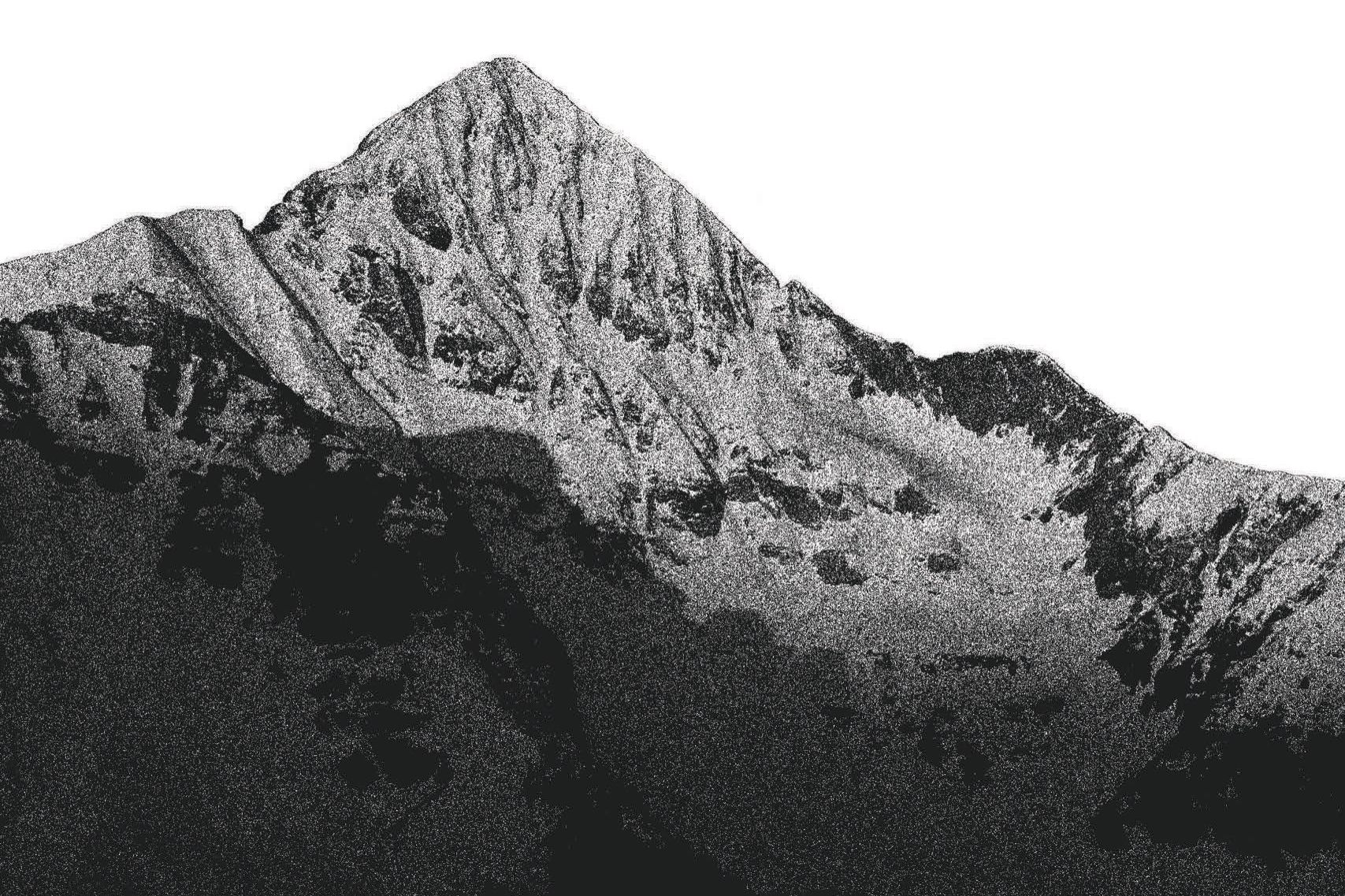

Race leaders jockey for position at Stage Five’s start from Breckenridge to Colorado Springs.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from cycling—as a kid sprinting my buddies on neighborhood streets, as a young American representing my country on foreign roads, as a veteran racer-turned-journalist covering the Tour de France—it’s that great races are wrought by great people with great ideas.

And it was greatness I sensed one cool, crisp late-summer morning last August as I made my way through knots of cycling fans assembled on the Riverwalk Center Lawn, along the banks of the Blue River in downtown Breckenridge. The 2012 USA Pro Challenge, a weeklong professional bike race, was in town gearing up for the start of its fifth of seven stages, and several thousand raucous spectators, many of them kids seeking autographs, were in attendance a block away, vying for glimpses of the riders as they assembled at the start line on Main Street between Washington and Adams Avenues.

Long before this day, organizers had encouraged towns along the race’s route through the High Country to create works of art commemorating the event. Breckenridge leaders had responded by commissioning Tim Mitchell, a local welder, to create what they called the “Bikeffel Tower,” a 30-foot sculpture resembling the Eiffel Tower in Paris, a sight every pro cyclist ever to compete in the world’s greatest bike race, the Tour de France, yearns to see. Mitchell, assisted by a crew from the Summit County Resource Allocation Park and Summit County Recycling, had taken on the challenge with aplomb, ultimately assembling an impressive work of art comprising pieces of scrap metal and parts from 150 used bikes. The soaring sculpture was, in my mind, the perfect connection between this fledgling bike race and that bigger, much more famous one across the Atlantic.

“I thought it was a great idea to link this event with the Tour de France,” agreed Mitchell as he marveled at the throngs gawking at the statue before the race started. “It means a lot to me. The best part is watching all of this.”

This was Breckenridge’s second experience with the USA Pro Challenge, a two-year-old event that already was being hailed by promoters and athletes alike as the most demanding bike race ever held on American soil. When this former mining town–turned–ski resort hosted the finish of a road stage from Steamboat Springs in the inaugural 2011 race, spectators were so thick on the day’s final climb up Swan Mountain Road—several miles before an exciting finish downtown—that some riders said they found it a challenge to ride through them. Scott Fortner, who represents the town’s business community as marketing director for the Breckenridge Resort Chamber, says he was even more ecstatic this time around. While retailers, hoteliers, and restaurateurs enjoyed an immediate boost to business again for the second year, he explains, what matters most to the community overall is the worldwide media coverage.

“We’re known as a world-class ski destination; this exposes us as a world-class cycling destination, as well,” Fortner says. “The emphasis is on international exposure. For us, it’s about not the short term, but the long term.”

“Either way, the attention we’re getting is phenomenal. They’ve nailed it two years in a row,” adds Breckenridge Mayor John Warner, a cyclist, skier, and serious outdoorsman. “I’m happy to see great crowds, and great press, enhancing our image, and Colorado’s image, as a cycling mecca.”

Back at the starting rally, to cheers all around, shots from a starter’s pistol pierced the festive mountain air, prompting the entire race entourage—riders, officials, support staff, promotional and media vehicles—to embark upon two quick, neutral laps of the packed downtown area before heading south in a dusty uphill whoosh on Highway 9 toward the summit of Hoosier Pass, at 11,542 above sea level, through Fairplay and Woodland Park and on to the day’s finish in Colorado Springs, 106 miles away.

With the glory of the high mountains, the huge crowds, sometimes hostile weather, epic climbs, and breakneck descents, this was, I realized, the same mix of beauty, excitement, and great ideas I’d witnessed as a young man racing in and reporting on the biggest bike races in the world. For a few minutes, I felt transported back to Paris-Roubaix, Milan-San Remo, and the other “grand tours” of France, Italy, and Spain. Except that this was Colorado—which could, just maybe, mount a bike race capable of rivaling them all.

Photos clockwise from upper left: Breckenridge Elementary School students await the Stage Five start; a Citizen Street Sprints competitor; retiring cyclist George Hincapie and a farewell message; Mayor John Warner; fans outside the team bus; watching Stage Five on the Riverwalk Center lawn; an exuberant fan; the Bikeffel Tower; a rider high-fives fans.

When I was a kid racing bikes in the mid- to late 1970s, the only American bike race to come close to emulating the great cycling contests in Europe was the Red Zinger Bicycle Classic, known later as the Coors International Bicycle Classic. Based in Boulder, that event, on an initial budget of about $100,000, ventured into the heart of the High Country every year, visiting Aspen, Vail, and Breckenridge on many occasions. Overall winners included some of greatest American cyclists of the era: John Howard, Dale Stetina, Greg LeMond, and Davis Phinney. In its glory years during the 1980s, promoters of the Coors Classic grew the race considerably, boasting at its zenith that the event was “the second-largest bike race in the world.”

But before the decade was over, the Coors Classic had fizzled. After Davis Phinney won it in 1988, the title sponsor bowed out. Subsequent stateside races met similar ends: the Tour de Trump, an East Coast stage race bankrolled in 1989 and ’90 by The Donald before DuPont funded it, endured eight years, and the 2000s saw similar, shorter crash-and-burn stories with multiday tours of Georgia and Missouri. It wasn’t until 2006, when Medalist Sports, the bike-race-logistics wing of Los Angeles–based sports and entertainment marketing giant AEG Sports, began the only other serious stage race in America, the Amgen Tour of California, that top-tier professional bike racing rode back onto the map in the US, inspiring young American cyclists like Taylor Phinney, Davis’s son, to join the professional ranks.

“Taylor’s getting the vibe now that we all got when we raced the Coors Classic,” says Davis Phinney, who happens to be a former rival and teammate. “It’s great to have big-time bike racing back in the US,” he added.

While America’s flirtations with cycling waxed and waned, Europe’s cycling spectacles only have gained momentum. For generations, the big three-week tours have drawn millions of spectators and thousands of international journalists every summer. Fans from around the world crowd onto wide city boulevards, cobbled farm roads, and lonely high passes hoping to watch their sports heroes throw down performances like Voigt’s.

To this day, the most celebrated climb in modern Tour de France history is the ancient, steep, narrow road famous for its 21 named switchbacks to L’Alpe d’Huez, a tiny French village and ski resort high in the Central Alps near Grenoble. As a journalist and a cyclist, I’ve been up and down that hallowed route at least a dozen times, either as part of the Tour de France media entourage or as a guest on one of a multitude of privately run bicycle tours. The high Alpine village is an annual pilgrimage for cycling fans from around the world, and every summer hundreds of thousands of them line its 8.5 miles to watch their heroes battle for the privilege of wearing the Tour’s yellow jersey to Paris.

Improbably steep and twisty mountain roads like that one are a key element of every great stage race, and Colorado has them in spades. The state’s lofty passes can challenge the sport’s most elite athletes, and its spectacular mountain vistas dazzle spectators. Ski resorts, meanwhile, are natural partners for big-time bike-race promoters, and in Colorado these resorts typically have the capacity to host huge stage-race entourages, which can number in the thousands. That’s welcome business in summer, an economic slow season when many mountain hotels, lodges, and condominiums sit nearly empty, and events that draw visitors in the thousands—who need gas, food, and other services as well—are sorely lacking.

Europe’s cycling extravaganzas dump enormous sums of cash into the local and national economies. And Colorado’s potential for profit caught the attention of AEG, which has a knack for spinning gold from a long list of sporting events, including the X Games, as well as live concert tours by the likes of Bon Jovi, Taylor Swift, and Leonard Cohen and festivals like Denver’s Mile High Music Festival and the Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival in California. AEG’s Medalist Sports arm tapped Shawn Hunter, a former executive vice president of the Colorado Avalanche and Denver Nuggets who’d also overseen the Tour of California, to create a blockbuster bike race through the Colorado Rockies.

“I came in at a great time,” Hunter told me in a phone conversation after the 2012 race. “Companies, from big ones like Nissan, United Healthcare, New Belgium Brewery, and Waste Management to smaller ones like Smashburger, were investing. When we saw that, we realized there was an opportunity to create the biggest, best bike race in America, perhaps the second biggest in the world.”

Hunter noticed European races were managed for long-term returns, using a diverse family of sponsors, instead of just one “title” sponsor, like the ill-fated Coors Classic. So he imported the model to Colorado, and he hatched a new element as well: the USA Pro Challenge’s festival area, which, at every start and finish area during the weeklong event, attracts racers and spectators to a collection of tents featuring sponsor brands and products.

Hunter also drew support from Colorado’s mountain communities, which threw their marketing dollars behind the stage-race concept. Breckenridge, for example, budgeted $150,000 in 2011, when it hosted the finish of a road stage from Steamboat Springs, and again in 2012 as the start of a stage to Colorado Springs. For 2013’s race, town leaders upped the ante another 50 percent or more, to as much as $275,000, encouraging the USA Pro Challenge to return for both the finish of Stage Two from Aspen and the start of Stage Three to Steamboat Springs. For the former, Mayor Warner said he personally pushed for the new, exciting finishing circuit that will include a “killer climb” up Moonstone, and then Bonnie Ford Hill, before descending for a final sprint for stage glory on Main Street downtown.

The inaugural USA Pro Challenge, according to Hunter, commanded a budget in the millions of dollars and generated an estimated $83.5 million in economic impact in Colorado in 2011. Plus, the tourism-dependent state received a coveted close-up, since the race broadcast Colorado’s mountain beauty to 161 countries worldwide. The next year was even bigger: In 2012, the race contributed nearly $100 million to Colorado’s economy, received 31 hours of television coverage on NBC and NBC Sports Network, and reached an international audience in 175 countries.

No less influential a figure than Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, an avid cyclist in his own right, got so excited about all of the positive economic benefits in 2011 that he proclaimed the week of the race every year The Colorado Cycling Holiday—an invitation, basically, to every cycling fan in the state to get out and cheer the racers on.

Declared the governor, “Any expectations we had for success were surpassed tenfold.”

The peloton rolls away from downtown Breckenridge, en route to Colorado Springs.

For most Americans success means money, and the USA Pro Challenge has so far proven to be an economic boon. But some Americans, namely Coloradans, embrace cycling purely for the sheer glee of slipping through the High Country’s thin air on two wheels. And that participatory passion may be just the element this race needs to take root and—where prior attempts have wilted—finally blossom into one of the world’s great cycling contests.

“This is a special part of the country, and the people here understand what the riders are going through. Heck, many of them have ridden Independence Pass themselves,” Frankie Andreu, a retired veteran of nine Tours de France and now a television commentator and columnist for Bicycling magazine, told me in the Beaver Creek press room after the peloton’s Stage Four race from Aspen to Avon last summer. “And when I talk with the riders—from Durango and Telluride, Aspen, and now here in Beaver Creek—they all tell me, ‘Man, I gotta come back here for vacation.’”

Phil Liggett and Paul Sherwen, the voices of televised bike racing on NBC Sports, were quick to agree. “This state is made for bike racing,” said Liggett, nearly out of breath after walking uphill to NBC’s satellite truck. “The people here are all fit ... and they have bike racing in their bones.”

“Like at the Tour de France, we talk a lot about the history,” Sherwen added. “We love the history here, too, like Doc Holliday and Billy the Kid,” he gasped, also struggling to breathe in the high-elevation air. “The riders tell us they love Colorado, the accommodations, the food, how the fans treat them so well.”

For their part, fans see the USA Pro Challenge as an excuse to celebrate one of the lung-powered sports that mountain towns already hold dear. During 2012’s Stage Four, which coursed through Minturn en route from Aspen to Beaver Creek, a thousand or so people had turned out in the small town to cheer German Jens Voigt as he crossed an intermediate sprint line in front of Kirby Cosmo’s BBQ Bar on the way to his Stage Four victory at Beaver Creek.

“I’m a bike groupie, one of the biggest fanatics you’ll ever know,” said Heather Schultz, co-owner of Holy Toledo! consignment clothing, as she waved some of the several dozen custom bike jerseys she had made with the shop’s logo just for the race. “These guys are megastars.”

And part of the race’s as-yet-successful model is that each community finds its own way to celebrate. In fun-loving, family-friendly Breckenridge, the rambunctious party mood that held sway at the Stage Five start-line festival area in 2012 hardly abated just because the cyclists had departed up Highway 9 toward Hoosier Pass. Events the rest of the day, organized by the local chamber, included citizen street sprints, a chalk art contest, bike stunt demonstrations, big-screen viewing of the race as it headed for Colorado Springs, and a free concert.

“When we heard Breckenridge was going to host this event, I thought it would be a great experience to integrate it into our teaching,” said Caroline Farkouh, a literacy teacher for Breckenridge Elementary School, as she watched four dozen fourth- and fifth-grade students compete in the street sprints last summer. “The kids are learning a lot about geography, languages, the whole international aspect. Participating, cheering on the riders, also has been incredibly team-building—and that’s part of our mountain lifestyle.”

I realized then that the USA Pro Challenge’s greatest challenge was to continue to cultivate that sense of ownership, to maintain and nurture the race’s strong links to the past. The heritage of great people in cycling history, including Colorado’s own Phinney family, runs as deep and rich as the veins of silver, copper, and other precious metals that initially helped establish many of today’s Rocky Mountain towns. Pair that history with the reasons most of us are drawn to the region today—stunning natural beauty, a pervasive ethos of adventure, and a world-class outdoor playground—and the potential seems as limitless as the Colorado sky.

In two short years, the USA Pro Challenge has charged hard uphill. With a third version revisiting our communities this August, it appears to have broken away from the pack of failed American stage races. But in the wake of those races, and in the face of other obstacles like cycling’s recurrent doping scandals, the road ahead has its pitfalls. Just as riders who have conquered the summit of Hoosier Pass must steel themselves for a harrowing descent, the stewards of the USA Pro Challenge’s future in Colorado have to recognize that they won’t be in for an easy coast downhill.