Panorama

Looking Back at the Wildfire That Threatened Breck Last Year

Burning question: What, if anything, was learned from last summer’s near disaster?

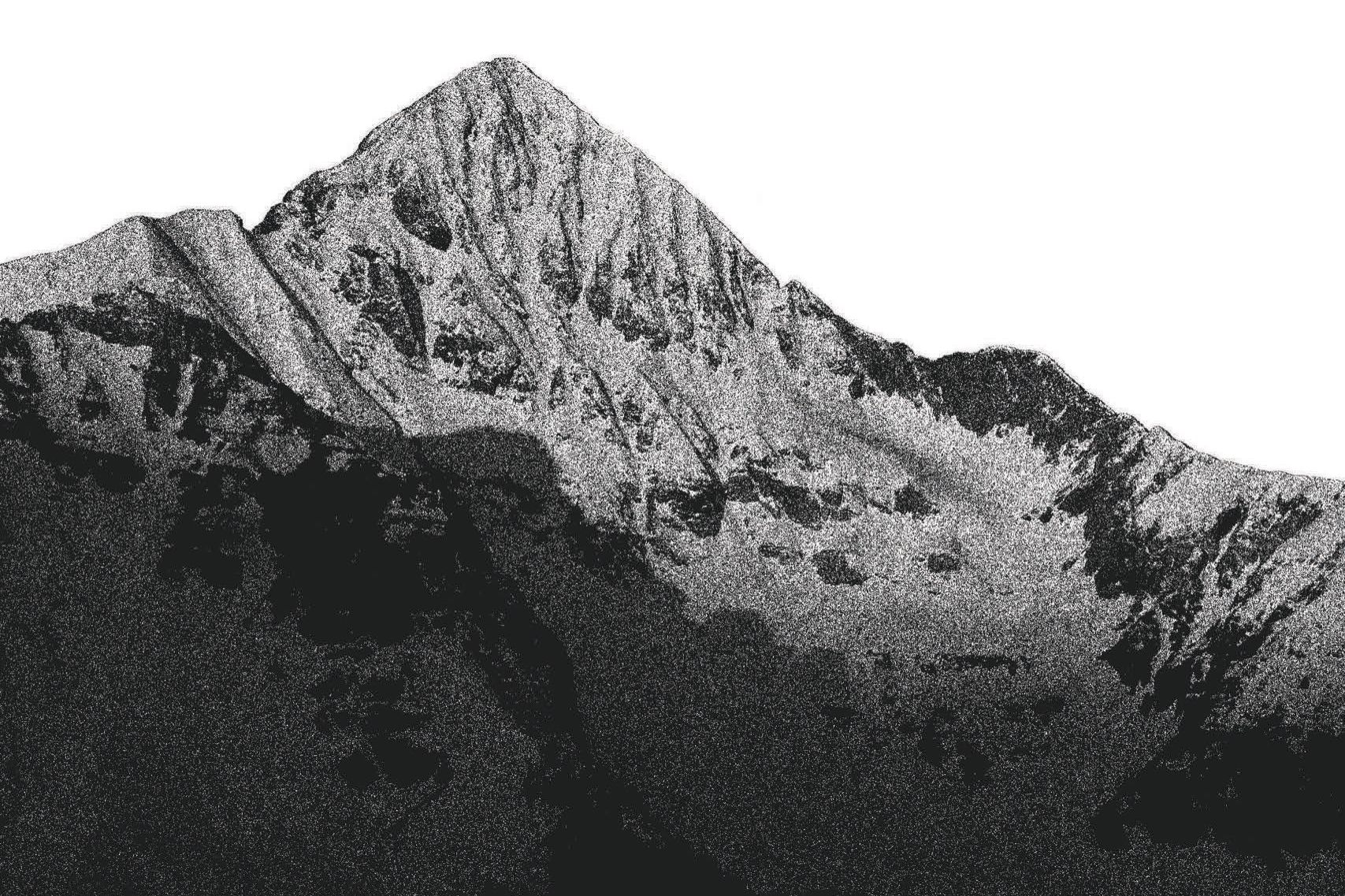

At 11 a.m. on July 5, 2017, a mountain biker riding in the backcountry between Frisco and Breckenridge called local authorities to report a wildfire burning just off the Miners Creek Trail. Tiny at first—perhaps 50 by 50 feet—by the time firefighters arrived at the remote location four miles north of Breck, the fire was leaping through the crowns of trees.

Fueled by dry timber and the hottest temperatures of the summer, the blaze, dubbed the Peak 2 Fire, created widespread panic as a wall of flames a hundred feet high raced south toward Breckenridge Ski Resort and the Peak 7 neighborhood, resulting in the evacuation of more than 400 homes. Fortuitous weather conditions and a quick response helped contain the fire in relatively short time; ultimately, the Peak 2 Fire scorched 84 acres of remote forestland and caused no damage to manmade structures.

With statewide forecasts predicting Colorado’s worst fire season in five years, largely due to a dry winter that left the snowpack at just two-thirds of average, this summer promises to be a tense one; anyone who witnessed that apocalyptic tower of smoke billowing at the edge of town might wonder how prepared we are—or aren’t—for another monster blaze.

The good news? Peak 2 validated years of work and cooperation among agencies large and small. “I would say Summit County is really in the vanguard in terms of counties being prepared for this kind of thing,” says Ross Wilmore, a former fire management officer who was responsible for all US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management acreage in Summit and Eagle counties. Wilmore retired after last season, but he assisted with the coordination of the Forest Service’s response to the Peak 2 Fire and others that preceded it. He says a number of proactive events over the past decade—including a practice evacuation of Peak 7 and successfully fought smaller-scale blazes on Ophir Mountain and in Brush Creek and Keystone Gulch—helped crews fight the Peak 2 Fire much more efficiently than they might have otherwise.

For years, a running joke among local firefighters was that Summit is home to an “asbestos forest,” meaning conventional wisdom dictated that our altitude and resultant higher humidity—compared with the Front Range and Grand Junction, anyway—provided immunity from a massive forest fire. That, combined with the fact that the mountain pine beetle hasn’t been active in the area since 2016, afforded a false sense of security. “We have learned our lesson; we don’t have an asbestos forest,” says Lake Dillon Fire-Rescue Chief Jeff Berino, who’s been fighting fires in Summit for 38 years. “From Peak 2 and the Tenderfoot Fire, we’ve learned that we are extremely vulnerable.”

The Noraka family enjoys a front-row seat of suppression efforts above Breck on the evening the blaze started.

The bad news? Lodgepole pine tracts like Summit’s live for about 130 years; want to guess what the average age is for a tree in our corner of the White River National Forest? “Summit’s lodgepole pines are at the end of their life cycle, so they’re dying off and falling down, providing that fuel bed,” Wilmore adds. “There’ll be a fire that will come through and start the cycle all over again.”

When that happens, we’ll be ready. Due to Summit’s high-dollar private property values, abundant federal resources, like the aircraft that helped contain the size of the Peak 2 Fire, remain available should another big blaze erupt. The Forest Service actually dispatched a Type 1 incident management team—the Navy Seals of wildland firefighters—to respond to the Peak 2 Fire. Usually reserved for blazes tens of thousands of acres in size, the Type 1 designation brought hundreds of elite firefighters, and a bill (footed by Uncle Sam) of roughly $1 million per day. That response may have been excessive, but it also proved a critical point.

“We learned that all of the preparations we had done were on the right track,” Wilmore says. “We are ready for the next one.”

Douse that campfire!

Fire investigators suspect, but haven’t been able to prove, that a pair of careless hikers ignited last summer’s Peak 2 Fire. With that in mind, in March, Governor Hickenlooper signed a law that increases penalties for leaving an unattended campfire, a prime fire hazard in the backcountry. What was once a petty offense dating to the 1800s is now a Class 3 misdemeanor with a fine of up to $750, plus potential jail time. The takeaway? Don’t just throw dirt on a fire ring before heading on your way; pour water on it until you can touch it with your hand.