History

For Whom the (Frisco) Bell Tolls

The history of one of Frisco's beloved landmarks.

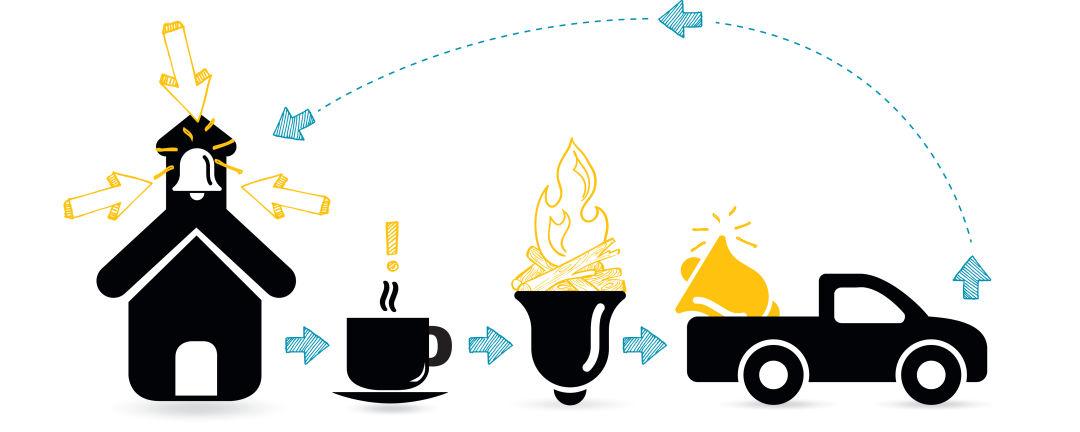

August 3, 1910

The Town of Breckenridge replaces its 1882 schoolhouse with a modern building; the cupola and bell are reinstalled atop Frisco’s one-room log schoolhouse, a former saloon, on Main Street.

August 11, 1975

While having his morning coffee at the Log Cabin restaurant across the street, School Superintendent James Beck looks out the window, notices the empty cupola, and exclaims, “The bell’s gone!” Under the cover of darkness, thieves had cut the rope and lowered the bell, weighing approximately 300 pounds, down the side of the school, leaving rope burns on one of the belfry’s posts and dents on the metal roof. “A crime has been perpetrated in Frisco that leaves Summit County residents indignant and dejected,” writes the Rev. Mark Fiester in the local newspaper, describing the stolen bell as “one of the most sweet sounding” in the county. A reward is offered for the bell’s return. It remains unclaimed for a dozen years.

Spring 1983

Resident Jeffrey Stephens purchases a mobile home in Breckenridge and discovers an old bell buried in the melting snow outside. Unfamiliar with the bell’s heritage, he takes it indoors, turns it upside down, and uses it to store firewood.

December 12, 1987

A visiting friend recognizes Stephens’ firewood bin as the stolen Frisco bell. Stephens calls the Frisco Police. In his handwritten three-page report, officer James K. Walsh (Badge 2463) notes that “Mr. Stephens believes that the bell he has could possibly be the same bell taken from the old schoolhouse in Frisco and if it is then he would like to see it return back to where it belongs.”

December 20-24, 1987

After comparing the bell’s markings with rubbings the Rev. Fiester had made before the theft, Officer Walsh determines that the bell is stolen property, loads it into the bed of his pickup truck, and hauls it back to the old schoolhouse in Frisco, where he finds the bell’s yoke, supports, and clapper in the building’s attic. With help from Frisco’s mayor, a team of carpenters, and the fire department (which loans its hook-and-ladder truck) Officer Walsh returns the bell to the schoolhouse cupola; it takes nine hours, in subzero weather, to finish the job. The town gathers outside the schoolhouse at midnight on Christmas Eve, and everybody looks skyward as the sweet-sounding bell echoes across the lake, pealing for a full half hour. “It was a cheerful, boisterous celebration of rather chilly, rosy-cheeked Frisco town members, including little kids who were allowed to stay up past midnight and a lot of elderly folks who remembered when the bell was first stolen,” recalls Officer Walsh, now retired on acreage outside of Silverthorne. “It was special. ... that night really meant something.”

Present day

Today, the only time the Frisco bell rings is when visitors to the Frisco Historic Park & Museum, which now occupies the schoolhouse, ask for permission, and pull on the rope that cascades from a hole in the ceiling. Perhaps that should change: what seems to be forgotten is that before the bell was stolen, the Frisco Chamber of Commerce had voted to ring it daily, and on special occasions—like midnight on Christmas Eve.